Historic Model—Gothic Binding

By Avery Bazemore

By Avery Bazemore

Students in the postgraduate Conservation of Books and Library Materials program are assigned a historic model project in their second term. It is probably the most universally loved assignment of the year. This year, Lucy made an Armenian binding, Jess made a Spanish ledger binding, Laura made a replica of the Faddan More Psalter, and I made a chunky Gothic binding with bronze corners, centerpieces, and clasps. I think they are all magnificent.

Gothic bindings were the last gasp of proper wooden board bindings. The style was popular from around the fourteenth century and tailed off in the seventeenth when the pressure to bind more books became too great to continue. Most Gothic bindings are on religious texts, because that was about all anyone cared about in the fifteenth century. Most books got parchment bindings, which were faster and less expensive to make. Laura's model is a good example of a ninth century style of parchment binding. Jess's is a structure that can be found in various states of development from the thirteenth century up to the ninteenth, although hers was designed to be written in after it was bound rather than as a binding for printed text.

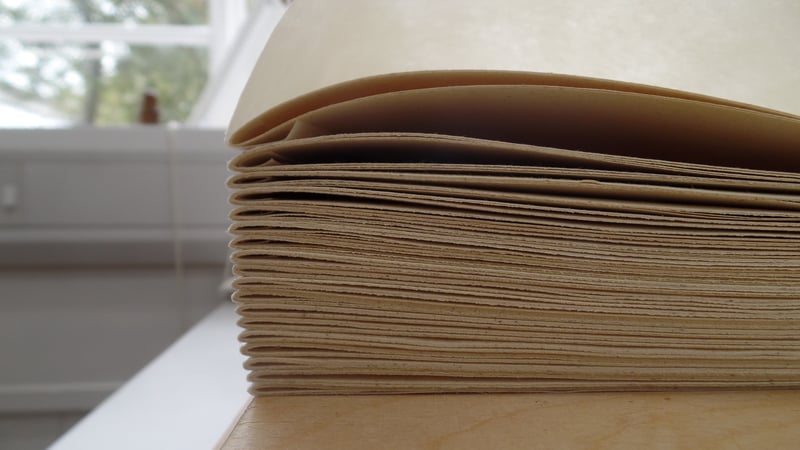

Early Gothic bindings were manuscripts on parchment, produced slowly by scribes, until the printing press was invented in 1440. After that there were a lot more books in want of bindings. Paper became cheaper and more abundant than parchment. Printers loved it, so that was another innovation binders had to contend with. Initially, binders did not trust paper to hold up when sewn, so they sometimes put little folds of parchment in the center of sections to keep the sewing from tearing through.

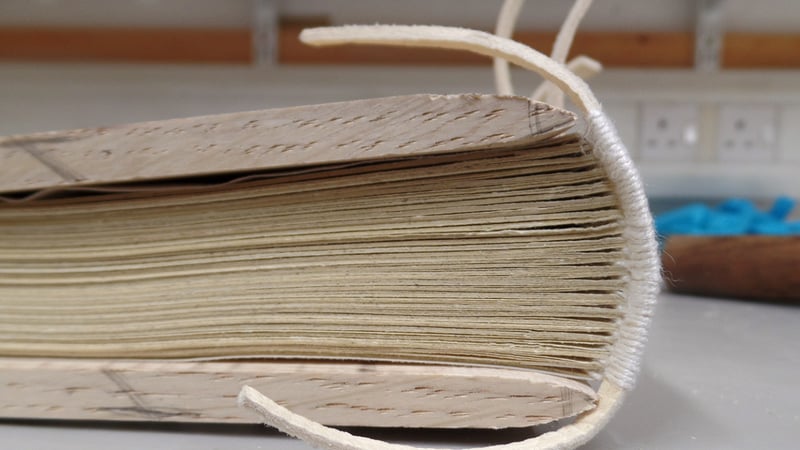

They were sewn over cords made of vegetable fiber or leather strips, which are then laced through holes in the boards. With cords, you can just drill holes to lace them through, but you need slots for leather thongs. I drilled a series of holes and filed out the area between them, then chiseled out channels for the thongs to lie in, which keeps them from being too prominent on the board after it is covered.

Gothic bindings were shaped to accommodate the natural round of the textblock. The thickness of the spine edge is greater than the rest of the textblock because of the thickness of the thread used for sewing, so it will slip into a round. Earlier Medieval styles did not account for this swell by rounding, and the spines often became concave through use. The boards of Gothic bindings were curved on the inner face to encourage a convex round. The outer face was shaped to create a smooth curve from the spine to the boards.

The book is covered in alum-tawed skin, which has a characteristic white colour and lasts for much longer than tanned leather. It is preserved using aluminium salts instead of tannins bound to the molecules in the leather. The alum can be washed out and the skin can putrify, so it isn't technically leather, but it makes incredibly durable bindings if kept dry. The sewing supports are also alum taw, so the board attachment is very strong.

Paring leather did not really occur to binders until the sixteenth century, so covering was a very straightforward process. I only needed to cut the alum taw to accommodate the laced-in headband supports, and mitre the corners.

Then my friend came to deliver the metal corners and centrepieces and clasps, which were historically bought in bulk by binderies. While most Gothic bindings did not have corner or centrepieces, nearly all Medieval bindings had clasps. Many have been broken or intentionally removed, but there is still evidence they were there. Clasps were important for parchment textblocks. Parchment is very sensitive to changes in humidity, and will warp unless it is kept under pressure. Paper does not move the same way, but binders probably saw no reason to change. They were usually die-cut or cast bronze, but my poor friend had to cut them all individually.

It was all worth it, though. It looks amazing.