By Tristram Bainbridge, Associate Tutor in Furniture

A historical craft practices project is part of the furniture conservation programme. Through engaging with historical practices we can develop our understanding of traditional joinery and for this project, the specific sensibilities of seventeenth century woodworking. The process of recreation enhances our ability to recognise specific techniques and tool markings on period objects. Over a period of four days in June, the furniture students made a joint stool, going through every stage from log to stool.

First off we need a good supply of green timber. Oak and ash are ideal for splitting because of their ring porous structure (concentrations of large vessels in the early wood area of the growth ring). Due to problems of supply we had to settle for a sycamore (acer pseudoplatanus), which is diffuse porous (the vessels are smaller and more evenly distributed throughout the growth period). Here is our recently felled tree awaiting preparation.

First the log was split into quarters using iron wedges and a sledge hammer. Wooden wedges or gluts may also be used to chase the split along the length of the log.

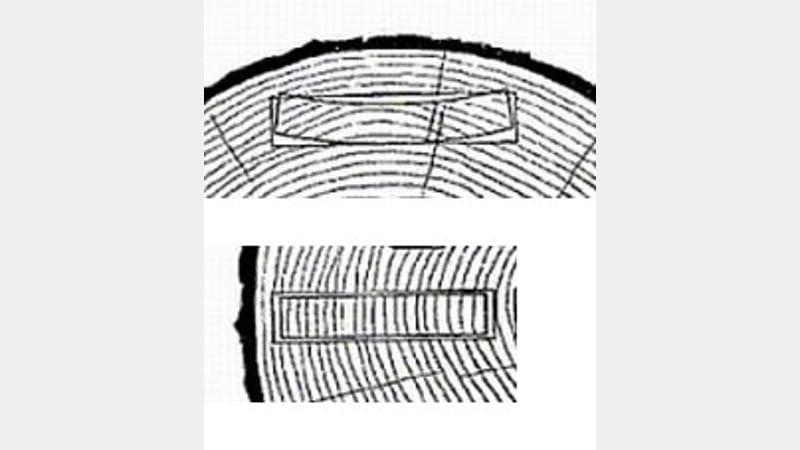

By ensuring all the stock is quarter split (with the growth rings perpendicular to the face of the piece) the maximum dimensional stability is attained. As the wood shrinks it shrinks equally on all sides and cupping and warping is avoided. This is exemplified in timber technologists' most favourite diagram.

Riving is the next stage, further reducing the size of the stock. A froe is used and the metal part is pounded with a big froe club (simply made from a surplus log) and the handle is levered to split the wood. The pith (small central section of the tree) and the bark and sapwood are removed. The froe is a surprisingly sophisticated tool and a wayward split can be redirected on good timber by levering the handle to and fro.

Rough dimensioning may be carried out with a hand axe. A series of angled cuts are made along the surface which can then be boosted out with a longer stroke. That way a rapid progress may be made.

The shaving horse can securely hold the stock as a flat face is created using a drawknife. A simple but effective clamp, it allows the wood to be quickly removed and adjusted but releasing foot pressure. The addition of a soft cushion under the operator's posterior would greatly enhance the experience.

A scrub plane can then be used to rapidly create flat and square faces. The plane blade is convex, allowing large thick shavings to be made. The characteristic scooped plane marks are often visible on period surfaces.

Jack and smoothing planes may be used for the final stages, although they were not always used traditionally (and they would have been wooden too…). During this period, once the show surface was flat and the two edges square to it, interior surfaces were often left riven.

To ensure maximum efficiency, each tool is used to its limit before moving on to the next.

After a supply of suitable dimensioned stock was produced, it was time for some practice mortice and tenon joints. Whilst some aspects of seventeenth century joinery may seem less polished to modern eyes, the joinery is highly accurate. Far more attention was paid to the squareness of the joint than to the smoothness of the finish.

With good straight grain the tenon waste can be simply boosted away with a wide chisel after the shoulders are cut square with a tenon saw. After a while of practice good accurate joints can be cut without needing to endlessly tidy up the joint with a shoulder plane or paring chisel.

The stool design was loosely based on this popular form. We would do a simplified version without turning the legs.

The stool awaiting its seat to be finished.

After a day's work. A pole lathe can be seen in the background but that's another story.