Conservator of Clocks and Scientific Instruments

Did you have a different career before coming to West Dean? If so why did you change career paths?

My background is in electronic product design and manufacturing, working mainly in radio, audio and acoustics for various ‘big name’ companies in the south and east of England and also a year working at the Siemens manufacturing plant in Vienna – our West Dean study visit to Vienna in March 2019 brought back pleasant memories of this beautiful city. Latterly, 10 years working in Cambridge on Tetra radio design for the police and emergency services.

I changed for more ‘hands-on’ mechanical work, to improve my workshop skills, and to study the theory and techniques of conservation.

Talk us through your career path since graduating.

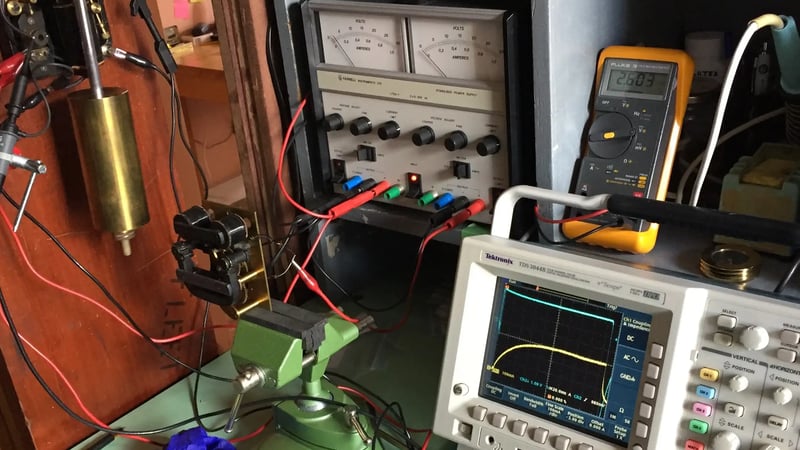

Given my background in electrical engineering I decided to specialise in early electric clocks, working as a self-employed conservator of clocks and scientific instruments. I had already established a small workshop at home, so in 2021 I got to work immediately on electric clocks for customers, which funded some improvements to the workshop.

My first project, which proved to be a baptism of fire, was a master clock from the 1920s by the Silent Electric Clock Company. It was in a poor state of repair and took several months to complete. The work included writing a treatment report which is now published on a specialist electric clock website. Following this, I worked on several other electric clocks and also established a capability to remagnetise permanent magnets.

Apart from electric clocks, I have a particular interest in the history of early radio and recently I had the opportunity to work on the first commercially available radio receiver manufactured by the Marconi Company at Chelmsford in 1899. Electronics didn’t exist in those days, so the device is entirely electro-mechanical. The receiver used a glass tube coherer to detect the radio signal, which had to be continually reset or decohered using a mechanical tapper. Following extensive research (see below) I made two replica electromagnet coils for the tapper, to original specification. This involved turning boxwood bobbins, soft-iron cores and screws. Each bobbin was then wound with 7,500 turns of fine wire to achieve the correct resistance.

What do you consider your biggest achievement to date?

This was my discovery, in 2022, that an object in the Marconi Collection at the History of Science Museum in Oxford is a replica.

As part of my research for the early Marconi radio mentioned above, I made a study visit to the History of Science Museum, where the Marconi Collection of historic objects is now kept.

I was surprised to find the Collections and Research Access Manager who looked after me at the Museum was ceramics alumna Melanie Howard, who left West Dean the year before I started. After further research and a follow-up visit, I became convinced that the radio held in the Marconi Collection was one of three replicas made for the Marconi Jubilee exhibition in 1947. I compiled my findings into a report for the Oxford Museum, which found its way to the Curator Emeritus at the London Science Museum who uncovered further information on the replica receiver, as it was on loan to the Science Museum for several decades.

What projects are you currently working on?

I have just completed work on an unusual electric clock for a London-based collector. Made by the Eureka Company around 1912, it has a distinctive very large balance wheel. Currently under test, it is keeping excellent time.

Another project is a French Horophone, which is an early radio receiver (c.1913) designed to receive accurate time-signal transmissions from the Eiffel Tower. These transmissions started in 1910 and, although initially established for navigation, proved popular with horologists in an age long before radio broadcasting when there were few sources of accurate time.

Currently I am conserving an early Marconi Morse code key from c.1912, of the type used on board the Titanic. I’m remaking one of the missing contact sets, which includes an insulator made from ivory.

Do you have any tips for recent graduates?

Your studies at West Dean are just the beginning – you will never stop learning. Ask questions, seek out experts in their fields and learn from them – often they will be pleased to pass on their experience to the next generation to keep our heritage alive.

Keep good records of all the projects you work on. A varied portfolio is useful for clients and job interviews. Detailed notes make invaluable reference material for future projects.

Work towards accreditation to ICON or your specialist professional body. As well as giving you recognition and credibility in your field, you will find a good support network.

How do you think studying at West Dean College prepared you for what you do now?

Learning all aspects of object conservation from research and observation, problem identification, treatment proposal, report writing, and of course the treatment itself. I developed transferable skills, applicable to many types of scientific instruments.

Becoming an object conservator has proved to be my ideal job. It suits my interests and personality – a desire to preserve or even ‘fix’ things, but done in an ethical and responsible way with due respect for the object, its heritage and its stakeholders. I find both the research and practical work equally rewarding.

What's your favourite memory from your time at the College?

- Working evenings and weekends in the workshop to (usually) dulcet tones emanating from the adjacent musical instrument workshop.

- The organised visits and making contacts with museum curators, collectors and conservators.

- Meeting fellow students from different backgrounds, countries and ages.

- Learning from other students about their disciplines, e.g. many clocks are housed in wooden cases, or have ceramic dials, or have specialist metal-related problems such as corrosion, and some even contain leather or paper.

- And of course the food.

Did you receive any form of funding to study at West Dean?

For my first year Graduate Diploma, I received some funding from the Edward James Foundation Bursary and the York Foundation for Conservation and Craftsmanship.

Returning for a second year to study for a Professional Development Diploma would not have been possible without generous funding from the George Daniels Foundation and the West Dean Horology Bursary.

Learn more about studying Horology.