Why mention this? Well because West Dean College of Arts and Conservation is about encouraging and facilitating creative endeavour. Edward James our founder was an incredibly prolific and versatile writer, perhaps someone who would have both appreciated and envied the notion of writing quickly. The Archives of the Edward James Foundation, housed at the College, contain an astonishing amount of writing by James. Beyond his official published works, it is dominated by an enormous trove of correspondence with some of the most notable cultural figures of the 20th century: Leonora Carrington, Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, Edith Sitwell, and many others.

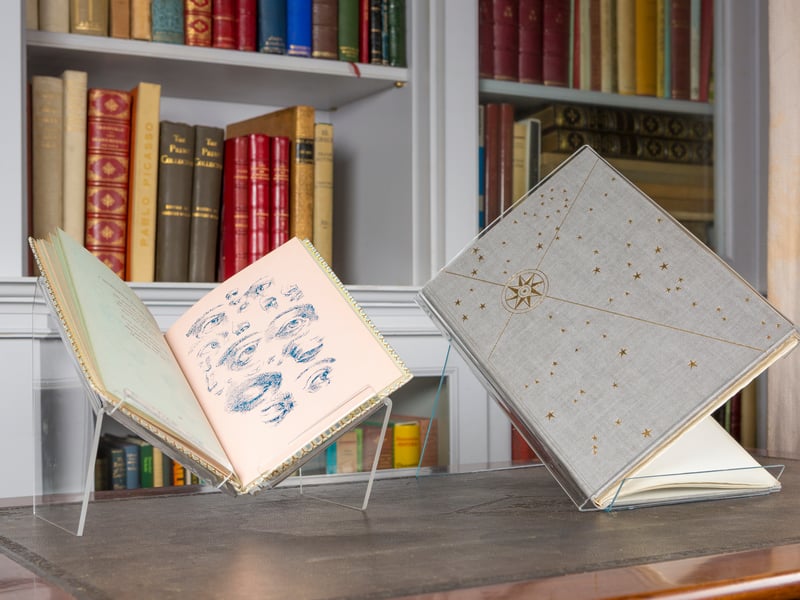

Having started composing poetry at Eton College, James published his first collection of poems at Oxford in 1926, when the author was only nineteen years of age. He went on to establish his own publishing imprint, The James Press, and in the early 1930s would publish over a dozen titles, often working with noted artists and illustrators such as Rex Whistler, Edward Carrick, Pavel Tchelitchew, and Oliver Messel. The James Press would also publish the first collection of poetry by John Betjeman, a friend from Oxford, entitled Mount Zion or In Touch with the Infinite (1931).

James would also work outside his own imprint, and in 1937 published a novel, The Gardener Who Saw God, through Duckworth in England and Scribner’s in the United States; and in 1941 another collection of poetry, The Sight of Marble, was published by Julian Messner in New York.

James’s publishing history is complex and idiosyncratic, often being produced under pseudonyms (Edward Selsey and Edward Silence among them) and reflecting his habit of ceaselessly revising books over many years. James explained his methods in a 1934 ‘Apologia’:

"It has been my practice with works that I have been unable to complete or which, when materially completed, have still appeared to me open to substantial improvement, to take advantage of my pleasure in fine printing by experimenting with such manuscripts – so out of such unsealed, unconsummated matter, I have tried to produce books which in their illustration and general production may achieve a degree of merit which the text itself may not yet have attained. Of such books I have had only a very limited number of copies printed, and instead of issuing them all, at once, for sale, I have thought more fit (after giving one or two copies to my intimate friends) to lay them by in my cellars as one lays up a stock of wine, to wait for it to arrive at such period when it can at last be reviewed in retrospect and drunk in that state of mature fermentation which only the patient years give. If this work had been left in its manuscript state I would have undoubtedly destroyed it, disheartened. The apparently extravagant principle has a reason and a method more thorough than might first appear to the ordinary run of commercially minded critics. For I get thus a view in complete perspective of my writing, seeing that when I take it out again after a few years I can gauge and observe it as I could otherwise only with the books of others. I am then able to produce from the ébauche a more perfected result, to be offered eventually to the larger world. Thus I would have you believe that it is rather from reticence and deference [diffidence] than from any inflated estimate of the value of my writing, that I produce these limited and private editions."

One can see even from this short note that, as well as being prolific, James’s creative process always remained open to future possibilities – much like the endlessly growing series of concrete structures he began to build at ‘Las Pozas’, his ranch in the Mexican jungle outside the town of Xilitla. Even as the

Lavish editions of the 1930s fell away into what John Lowe would call the ‘roadside publishing’ of later decades – writing on the move, making use of various city printers on his endless travels, producing pamphlets and chapbooks – James’ written output increased.

As well as innumerable unpublished fragments of poetry and prose, he continued to compose copious letters to friends all around the world, many unsent, essentially taking the place of an autobiography that would never be written. The Archives at West Dean contain much of this material and, it is hoped, further research will allow us to appreciate the full range of Edward James’ writing and understand more fully how it represents his unique creative voice.

Whilst convention might suggest we notice the finished work of an author it is often worth giving a little attention to both the process by which they got there (false starts, distractions and abandoned drafts included) and (as Edward James’s archives illustrate) the range of work that emerges when someone simply ‘does the work’. The key seems to be to commit to work; nobody knows what will emerge once that work begins, we just know something is produced.