In and around the wider West Dean Estate there are various landscape features, sites, architecture, objects and events that relate to art practice and artworks in different ways, from deliberate interventions, potential sites for installation, natural locations (or earthworks) that take on the presence of artworks, or indeed surreal settings that conjure up the life and legacy of Edward James with images reminiscent of the Surrealism he patronised. As this series of blog posts will show, more than a few of these offsite oddities in and around the College form part of the fabric of West Dean, providing students with points of reference, inspiration or destinations for excursions. One major manifestation of such sights, one that comes right to the gate of the College (indeed even further onto the main lawn), is the work of renowned British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy. His placement of over a dozen chalk stone along a five-mile stretch of the South Downs, linking the crest of a hill outside the village of Cocking to the West Dean estate, is a point of fascination for anyone with an interest in his practice or keen to take the walk.

Produced in 2002, Goldsworthy's project was developed as part of the Strange Partner's programme, involving the Edward James Foundation, Pallant House Gallery, The National Trust and Chichester District Council amongst others. The trail is distributed along a network of Public Rights of Way, moving through West Dean woods via a combination of footpaths, bridleways and byways. Following the route takes you through rich countryside, including managed fields and woodlands, forests of larch and beech, hazel coppices, as well as designated nature reserves and open farmland. Climbing to various peaks along the Downs, there are views not only of West Dean but of the Cowdray Estate to the north. Goldsworthy's series of boulders appear on the trail like oddly bloated distance markers. They were sourced from a local chalk quarry, possibly just behind the start of the trail, visible as a toothy smile in the hills beyond the A286. They are shaped in rough-hewn spheres, although many sit heavily in the undergrowth, their dimensions often hidden or reduced amongst foliage. As a set, the appearance of the stones is broadly similar and yet curiously singular: not one boulder exactly resembles another, nor does one emerge as more important or significant (to the traveller?) than any other. There are occasional tool marks still visible on their matted surfaces, together with bright glimpses of whiteness, yet the overall patina is one that is already softened into lichened grey beneath the elements.

It is interesting to ask to what extent the placement of these chalk stones might be 'strategic' and where such a strategy might be pointed.* We might also ask to what extent is it possible or necessary to speculate on the decision-making behind the depositing of such enormous, weighty objects, and whether there were particular aesthetic considerations in play concerning designed vantage and views, compositional and conceptual grammar implied in the stones' sequence or indeed whether the intervention is best served by the boulders half-disappearing into the landscape, creeping up on the wanderer, or being conspicuous on a guided route. This uncertainty of status is perhaps what lends the experience of coming across the stones most compelling. The stones emerge into view in different ways for each walker, dependent on all manner of contingencies, such as time of day, direction, whether they are sought or chanced upon. Yet for the most part they occur like an incongruous emanation, made up of a substance that seems perfectly familiar yet also unknown in such places. They become still and silent visitors, materialisations of that kind of otherness common to many surrealist motifs and theories of unconscious emergence. Perhaps Goldsworthy's comments about the use of chalk is important here, as he acknowledges that, for him, it is a substance that has unusual properties. Many of his works, firmly connected to the specifics of where they are placed, emphasise the material qualities particular to that site. His choices here address the rounded sweeps of the Sussex Downland whilst citing his own experience of intervening in other landscapes, especially those of contrasting geological make-up, highlighting the difference in experience when "digging a hole and finding it white (...) finding the sky in the ground"**. Such descriptions, whilst arguably oversimplifying a landscape by instantly making it subject to comparison, triggers something of the counter-intuitive denial of expectations that is present in much surrealist art. The uncanny appearance of these boulders-not only their tassled and flaking surfaces but their distribution across the land-links a unexpected inversion of 'sky' and 'earth' but links directly to motifs used by artists patronised by West Dean founder Edward James: the enormous, gravity-defying boulders in the work of René Magritte.

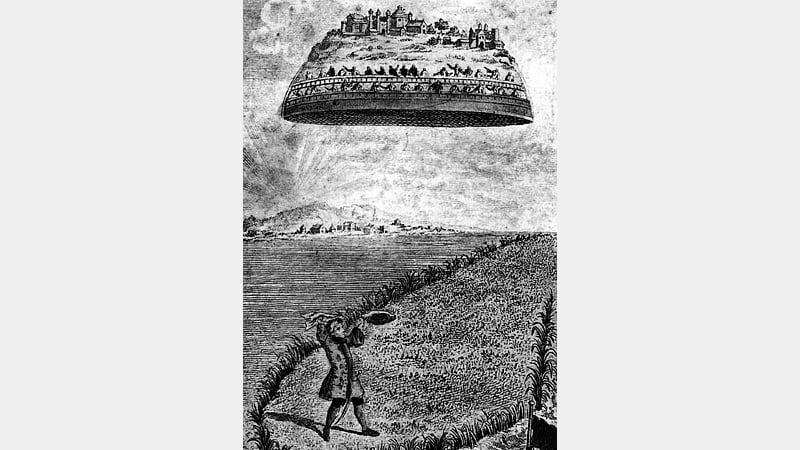

Odd though it may be, this is a more common image than we might think. The sight of a pitted rock, suspended in the firmament, visible by day and by night, should not be so shocking to us given that we are accompanied almost constantly by the puckered face of the moon, visible at different occluded angles. Part of what might be involved in making the journey between the chalk stones is the underlining of our acceptance of the stability of integrated orbits, suddenly being reminded of the strangeness of being hounded by this satellite, an oversized rock circling the planet like a gadfly or a bolt from a catapult. It is also not difficult to see the sequences as just that, a sequence, relating to the phases of the moon, even a timekeeping device, as much to navigate through time as across the Downland. The chalk stones' relationship to the air seems insistent-perhaps it is this that motivates their oddity-as they were strange because they have 'crash landed' or were in fact at any moment about to soar into the sky. Perhaps they are remnants of an airborne context, fragments of defences from the floating city of Laputa in Gulliver's Travels.

These may or may not be the type of mysteries that the artist hoped to harness. Goldsworthy is primarily an artist of the environment, celebrated for localising natural materials in order to create transitory sculptures and landscape disruptions. His discrete lumps of Downland chalk along the trail certainly serve to signify the extending mass of material running beneath the South East of England, from tilted scarps to white cliffs (often with images carved into it). Goldsworthy's use of these punctuation markers might indeed imply something of the strangeness of geological time. Chalk is constituted from calcium carbonate scale deposits of sea creatures (Coccolithophorids) transformed into microfossils, generating a soft, porous white matter of numerous uses, from heavy industry to the fine arts. But what the walker also comes across are extrusions of the deep-sea into the managed landscapes of contemporary farmland estates. These are the kinds of folds in time that are actually found to be commonplace, taking place everywhere we look, yet serve to remind us of timescales outside of our experience, spaces beyond our grasp. Perhaps the chalk stones resemble more than anything a series of meteorites and we should heed the warning of the title character in Patrick Keiller's film Robinson in Ruins, that meteorites "fall at a time of significant events".*** Of course, Robinson is concerned with the Wold Cottage meteorite, which fell on Yorkshire on 13th December 1795 (a time, he argues, when amendments to the Settlement Act were allowing capitalism to develop faster in England)-yet it is worth noting that that meteorite embedded itself, rather ironically, in chalk._____

* Graham-Dixon, A. (2002) 'Chalk Stones Trail by Andy Goldsworthy', Sunday Telegraph

** Ibid.

*** Keiller, P. (2010) Robinson In Ruins. UK | Colour | 101 mins