As mentioned in previous posts on this blog, the current exhibition at Gallery SO in East London is Fix Fix Fix. Curated by Glenn Adamson, Head of Research at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the show focuses on the interrelations and distinctions between the worlds of art making and conservation, bringing together commissioned and privately produced objects related to the theme of repair. It involves work by artists working across a variety of media, as well as professional conservators. As part of the opening event earlier in the month, Jasmina Vuckovic, a graduate of West Dean College's Conservation of Ceramics programme and a representative of Sarah Peek Conservation, demonstrated her skills, joined on the night by the current Programme Leader Lorna Calcutt. A write-up of the event was recently posted on the West Dean Conservation blog.

Gallery SO is an intimate space. Its narrow facade is notable for the painted-brick sign above the ground floor window, the trace of the old twine merchant's and one of the last Jewish shops on Brick Lane (an apposite reference considering the theme of repair). This window looks into the front showroom, which nowadays displays work by international artists and makers; the rear showroom, where Fix Fix Fix is installed, lies beyond a small internal courtyard and specialises in temporary projects and exhibitions. Gallery SO is partner to another space in Solothurn, Switzerland, originally founded by Felix Flury in 2003. The gallery describes its main focus as the "contemporary object" and is especially associated with artists whose practices involve aspects of jewellery making and craft-based production. As such, it seems uniquely positioned on the 'boundaries' between disciplines, especially those of Fine and Applied art, in a way that is complementary to West Dean Collage. It is able to pose conscious questions concerning the distinction between ostensibly disparate worlds, drawing on their affinities and differences - such as their use of materials, their modes of display and visual language - seeking out potential overlaps as productive territories for curatorial work.

Fix Fix Fix is another ambitious example of such a show - one that straddles what could be considered separate endeavours of making and repair. Importantly, it draws upon artists that regularly exhibit at the gallery - such as Bernhard Schobinger, Lisa Walker and Hans Stofer - but brings them into contact with professional conservation and repair companies (such as Arlington Conservation, Fixperts and Park View Motors), specifically commissioned artists (Alice Kettle, Laura McGrath and Jasleen Kaurand, amongst others) and educational partners (such as West Dean). As a result, the theme of repair is therefore approached in various different ways throughout the exhibition. The curatorial statements link it, from the beginning, to the concept of an 'ideal' repair - an action that would leave no trace, restoring a damaged object to its original state through what is described as a process of "self-erasure; the more skilled the repair, the less visible it will be." This is also acknowledged from the outset as an impossible task, one that can only be idealised, and it is in fact this area of shortfall that opens out areas for artists (or art objects) to explore. The artist may have no desire or requirement to make their interventions 'disappear' into an original object, yet this paradigm may still have its attraction. In an artistic context, perhaps, this gesture - although it may borrow its materials or technologies - is not repair in this sense but a gesture of creativity within given constraints. Of course there may be an intention to re-establish a functional connection between the components of a given situation - to repair and restore - yet this may be made more or less explicit according to the artist's intention.

As well as the theme of self-effacement, contributors to Fix Fix Fix have also engaged with the theme of repair through connections to improvisation - how constraint can be an impetus for invention and creative solution. Many pieces draw associations from the short-cut, the jury rig, the bodge versus the botch (the former being British slang for a job improvised with whatever is to hand, the latter being a failed attempt), reverting to string, tape or unlikely materials, even cannibalisations of different items - all of which bring to mind the elaborate constructions popularised by Rube Goldberg and Heath Robinson, often associated with war shortages - making the best of things when resources are rationed. It is no surprise that Adamson makes reference to Richard Wentworth's Making Do and Getting By, a series of photographs that document the invention at work in the solving of everyday problems - which often call upon innovative approaches to the juxtaposition of materials, an expressive mixture of formal qualities and strangely poetic redefinitions of function.

Of course, this theme also makes reference to the expansive tradition of bricolage in the arts, yet the alignment with the professional approach to repair throughout the exhibition seems to open up more specific approaches to objects, more intimately connected to themes of purpose, function and decoration. Not only do the works draw upon a D-I-Y aesthetic but also refer to specific interventions into commodities, such that mass-produced objects can be transformed into unique (art) objects. One version of such an approach is employed by Lisa Walker, whereby she adapts a specific tool by radically abbreviating its original dimensions, yet crucially reinstating its operative function. Another artist might appropriate the exposed space of a breakage - the rupture in a ceramic bowl - in order to secure another surface area (previously hidden inside the object) that can now be used - in this case filled with writing (Hans Stofer). An additional function can be bestowed on a broken object, even if its original purpose is never reinstated.

Other works play on these limits of given function by redefining a repair according to apparently superfluous degrees of ornamentation. Such an approach can involve mimicry, whereby the visual appearance of repair/damage is reproduced in another medium - for example, cracked glass being 'faked' in etched silver, relying on the artist's hand to convince the viewer that the sinewy lines are in fact evidence of the stress fractures particular to the impersonated material. there are other examples where the traces of additional repair work have been otherwise hidden (explicitly or implicitly) by superimposed decoration. throughout there are questions as to whether fixing can be a form of annotation or commentary on what is already there, in all its complexity (which puts one in mind of the work of a recent visitor to West Dean's Visual Arts department, Bouke de Vries).

Other artists in the show create strange, surreal partial-objects, that are suggestive of function that has yet to be assigned. Whether this purpose is for the repair of some other object (one that is not present) is left unexplained. Such objects have a loaded quality to them, an air of anticipation that adds to their oddity. This strangeness is also present in works that come about when the parameters for judging the success of a repair in one context (such as a degree of 'polish' or the flattening out of inconsistencies) are used to deny the fundamental elements of an object in another. Again this plays on the subtle distinctions within the concept of repair, especially when they are taken out of context - for example, the different languages of preventative and corrective repair, or the interim repair vs. the wholesale renovation. The exhibition as a whole draws upon these fascinating details - often referencing the amount of knowledge that is required to understand an object - the materials and methods that were used to produce it - before any repair is undertaken, or the ingenious purpose-built structures that are developed for repair access. The centre of the gallery is dominated both by a grand piano suspended in a viewing truss, and a reconditioned jeep engine placed high on a plinth so that the barely visible traces of its repair disappear in plain view.

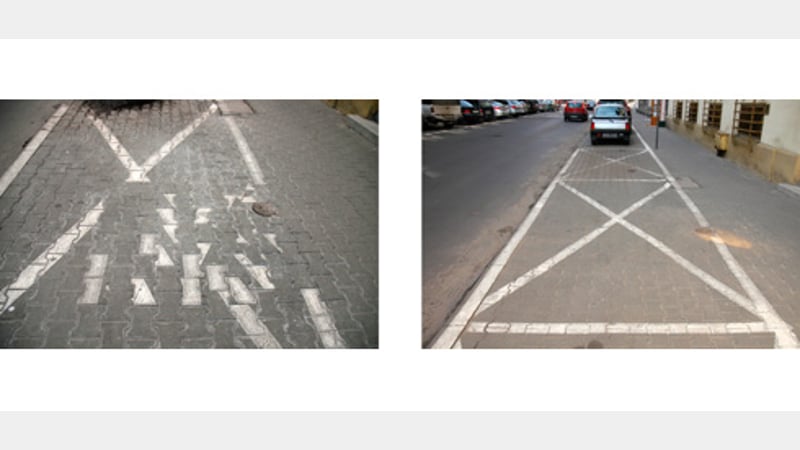

Yet one of the strongest themes to emerge from the exhibition is the consideration of repair as an act of generosity, tied in with a spirit of community associated with the common use of objects, spaces and systems. Such systems could be those related to value or exchange, wherein material substances become moulded into cultural artefacts and signifiers, distributed according to a shared language of responsibility, etc. - what might be described as the fabric of things. The Swiss artist Roland Roos, in his piece entitled Free Repair 91 (2008-2010), presents a double slide projection showing 'before' and 'after' images of what he calls his "unsolicited corrections" to the urban environment: repairs to civic spaces (car parks, pavements, walkways, railings and so on) as well as commercial indicators (shop signs, billboards, logos). Both these types of space are treated equally, without distinction, which suggests that Roos' reparations are intended to function outside any obvious political emphasis. The notion of solicitation is also central here too, in that the artist is assuming a particular role yet the parameters of the intended action are awkwardly defined; it is the artist's recognition of the necessary task that shapes the work, and that gives it is closure. Here there are interesting questions about how clearly an 'error' or fault is recognised by an autonomous individual, and the point at which that individual takes it upon himself to do something about it, indicating something of a moral or ethical investment in the common good as well as an established system of 'received ideas' that can be seen to be lacking given the right circumstances.

As with all of the pieces included in Fix Fix Fix, Roos' work is concerned with visibility. The presence of any repair, however it is approached or disrupted by an artist or conservator, by a curator or a gallery visitor, is directly concerned with close observation. Across all the pieces including in the exhibition, the theme encourages a form of scrutiny that links the contemporary object to its inherent material qualities and its weight of encoded information - data that can be repaired, extracted or otherwise manipulated in an infinite number of ways.