An interesting project came to the Books department last week: Brittany made this beautiful silver case for a tiny automaton, and the client asked for it to be covered in shagreen. We use a lot of different skins on a regular basis, but this one is unusual:

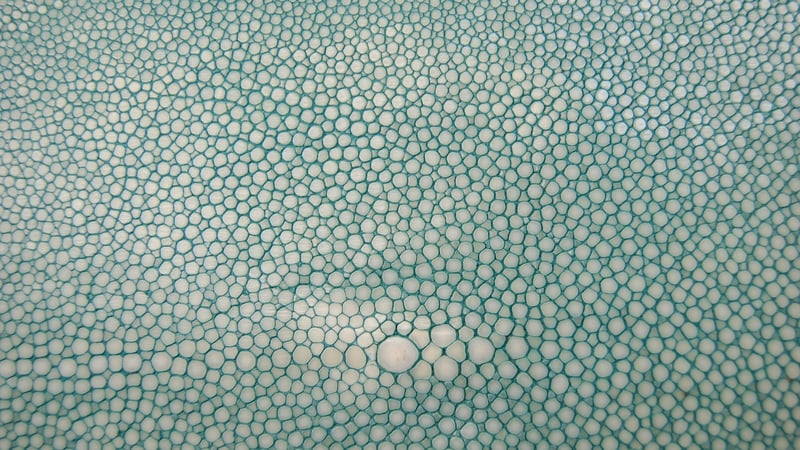

Shagreen is a bit of a loose term for a range of rough-textured skins. The 17th century Persians made it by pressing pebbles or seeds into horse, camel, or donkey skin to give them a bumpy grain; since then it has been used for a variety of coarse-grained skins. Now it most frequently refers to the skins of rays as well as (less frequently) sharks, dogfish, and other cartilaginous fish. These are covered in protrusions called placoid scales; they're very similar to teeth, with an inner core of pulp surrounded by dentine-like material and a thinner layer of enamel-like material. In Japan shagreen was used (undyed) for sword handles and armor, and in China for bows, in both instances its texture offered the user a better grip. In Europe for a long time it was simply an inexpensive byproduct of the fishing industry, used for abrasive: check out the description of making this modern shagreen sanding block.

Though it had been imported to Europe for about a century already, in mid-18th century Paris Jacques Galuchat popularized green vegetable-dyed shagreen when he covered hundreds of small objects for Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour. The material experienced a renewal in the 1920s on Art Deco furniture and small objects, often either green or undyed. The skins are small to begin with, and the useable parts even smaller, so it tends to be used to cover only small items, or in multiple panels if on furniture: there are some nice photos here.

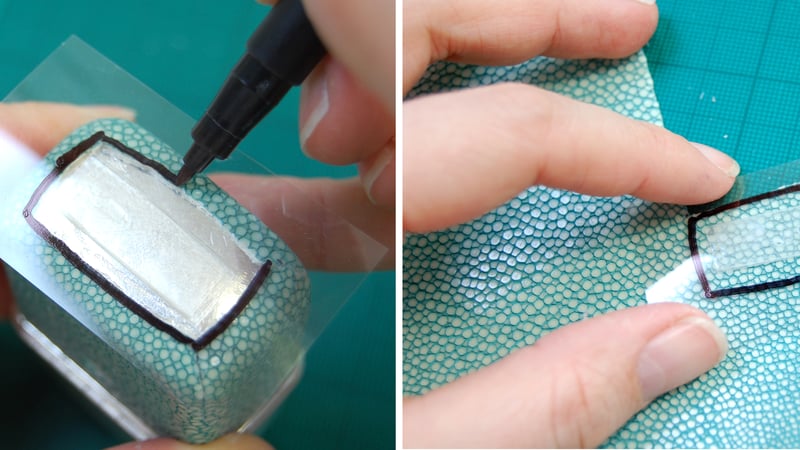

Shagreen is prepared by scraping, stretching, and drying the skin rather than tanning or tawing it. When used for decoration rather than grip, the dermal denticles are usually sanded down flat, as in the skin above. This one is an adult ray from Ed Tanner in London. You can see that the (vegetable) dyes are largely picked up by the skin rather than the scales, which are larger on older animals. Rays also feature this knot of bigger, thicker scales along the spine. The bigger the scales, the more difficult to cut the skin in a straight line: they're hard and brittle, and put up a fight when subjected to my breakaway knife, whose blade had to be changed constantly. Conservation and identification was covered quite effectively by Margot Brunn here on the Conservation DistList. Since Brittany's case was new, we didn't have to consider adhesives and ethics as carefully as if it was original to the automaton.

On to the covering: