by Roger Williams

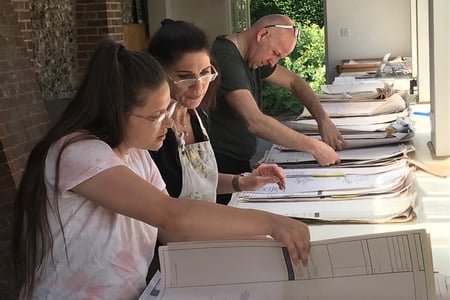

Aging of verdigris samples

In the first part of this blog post, I went over my process for making my own verdigris samples. I set these in the windowsill near my bench in the books department to soak up some daylight. After six weeks of aging, they already display a significant change in colour. One can imagine how much they will continue to change as time goes on.

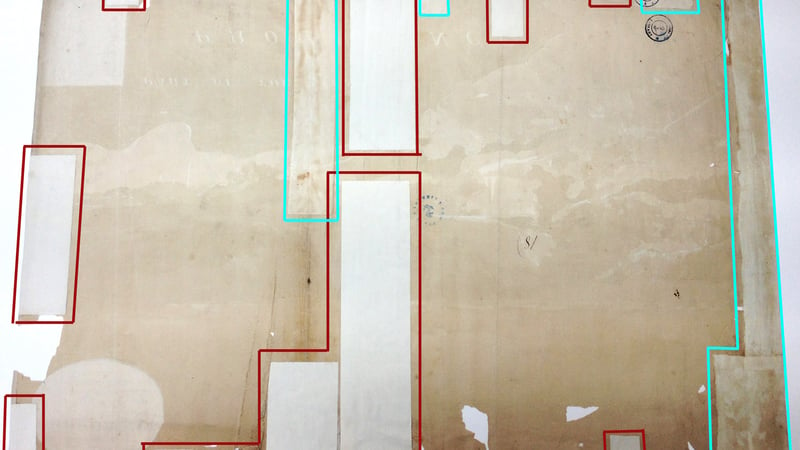

Removing old repairs

Before making my own repairs on the Gascoigne chart, I had to take care of the issues caused by previous repairs. The chart had two different types of old repairs, obviously from two separate previous repair attempts: some made with a handmade Western paper, and others with a much stiffer, machine-made, clay-coated paper. The repairs made with handmade paper seemed to be in fine condition and weren't causing damage. I decided to remove the heavier repairs, though-their adhesion was weak, they were blocking access to many tears in the chart, and their stiffness seemed to be causing more tearing in the brittle paper.

I was able to pull off about 90% of these repairs mechanically without any solvent, since their adhesion was so fragile.

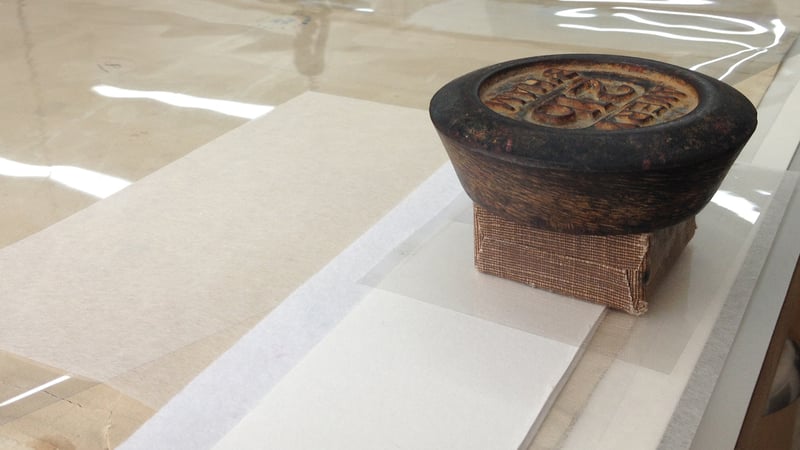

For the remaining bits, I used a Gore-tex® system to gently moisten the adhesive, which appeared to be a thin animal glue. Gore-tex is a synthetic fluoropolymer used primarily in the manufacture of performance wear and cable insulation. The polymer's microporous structure only allows water molecules of a very small size to pass through, making it useful in situations where only a small amount of moisture is needed. My Gore-tex system involved a sandwich of the following materials:

- A small weight

- Melinex® (polyester film)

- Damp blotter

- Dry blotter

- Gore-tex

- Lens tissue

After about five minutes of humidification, the adhesive was softened to the point that the repairs came away quite easily.

The remaining adhesive was moistened with an agarose gel and lifted with a cotton swab.

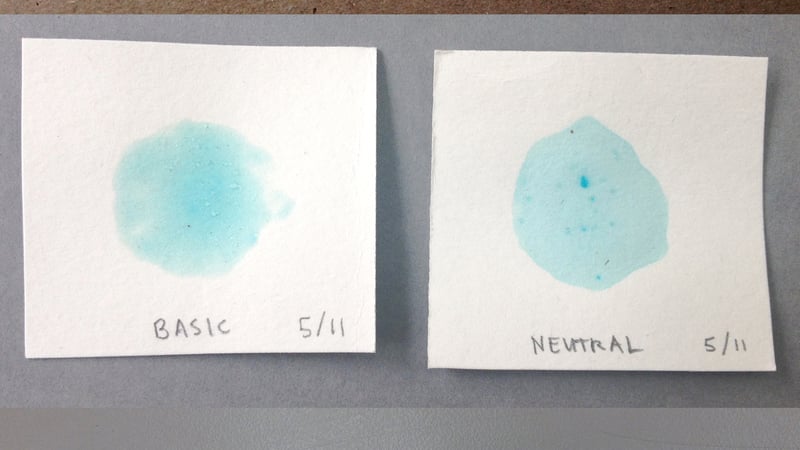

Preparation of re-moistenable tissue

To avoid adding excess moisture to the chart, which would only serve to speed up the oxidation of the cellulose polymers, I decided to use the re-moistenable tissue process described by Abigail Quandt (of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland) in her handout, "Remoistenable Tissue for Mending Paper Damaged by Copper Pigments," prepared for the 2002 International Institute for Conservation meeting held in Baltimore. This process involves applying adhesive to a light Japanese tissue, allowing it to dry, and gently reactivating it just before application. This introduces far less moisture than the typical wet wheat starch paste repair.

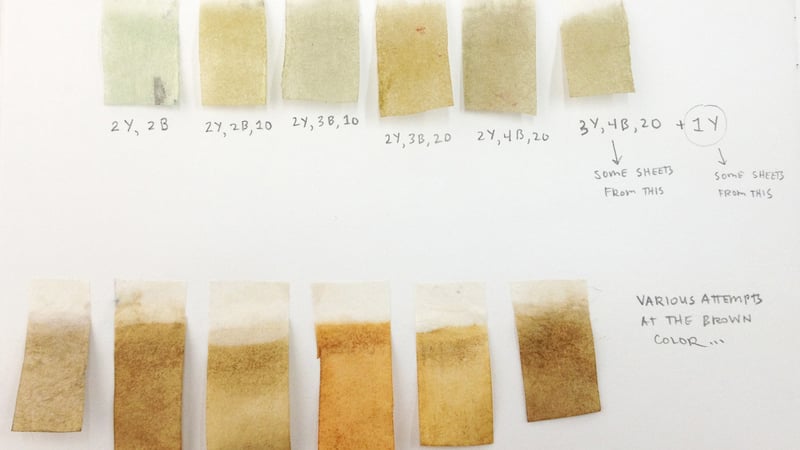

Before applying any adhesive to my tissue, I needed to dye it to match the chart's range of colours. The purpose of this colour matching is not to fool the viewer into mistaking the repairs for original material-the tissues simply needed to be shaded to avoid visual interruption, while also being an unmistakable addition. (Anyway, achieving a perfect colour match of the opaque chart would be nearly impossible on the partially transparent Japanese tissue.)

I chose two weights of Japanese tissue for the repairs: a very light kozo at 3.5 grams per square meter (gsm) to be used over basic tears, and a medium-weight kozo at 10 gsm to be used as in-fill material.

I used Cartasol® paper dyes 20% v/v in water, and dyed a series of sheets in a wide range of greens and browns.

Jin Shofu wheat starch was cooked 10% w/v in water. After cooling and straining, the paste was carefully thinned down with deionized water, using a Japanese wooden mixing bowl and paste brush. This mixing had to be done quite slowly to avoid lumps. After reaching the consistency of skim milk, the paste was mixed with an equal amount of 3% w/v methyl cellulose.

For each sheet of Japanese tissue, the adhesive mixture was laid down onto a Melinex sheet using a screen printing screen and squeegee. The tissue was then placed onto the thin layer of adhesive mixture, avoiding bubbles and brushing away wrinkles.

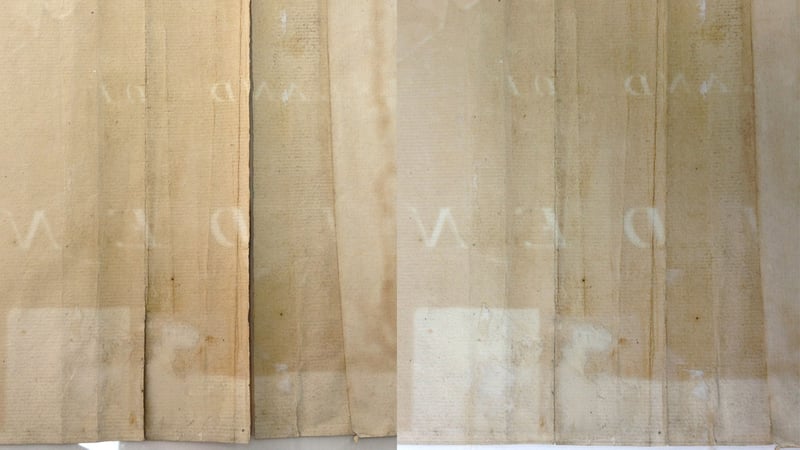

Repairing the chart

The tissue was ready to use after a day of drying. Having dried the tissue onto Melinex, the tears in the chart could be easily traced, and the tissue easily lifted. To reactivate the dry wheat starch paste/methyl cellulose, I dabbed the tissue onto a damp piece of blotter paper, then reduced the moisture a bit by touching it to a piece of dry blotter. I then laid the tissue onto a tear with tweezers and a bonefolder. A piece of dry blotter, protected by a piece of Bondina® nonwoven polyester fabric, was pressed onto the repair with a weight to speed up the drying. Each tear received two or three layers of the 3.5 gsm tissue.

I began with the tears along the chart's edges, working from the verso, then moved inwards to the larger tears that spanned the paper's length. The repair tissue successfully blended into the chart paper while providing strong support.

I then reattached any shards of the chart that I had found loose, using the same method. For these reattachments, re-moistenable tissue was applied to both sides of the chart.

My final step for the repair process was the infilling. I used water tears on the heavier tissue to avoid harsh edges around the repairs. This tissue was laid down with a light layer of wheat starch paste/methyl cellulose mixture and dried. A layer of the 3.5 gsm re-moistenable tissue then went over the entirety of the infill paper on both sides of the chart.

Housing

Once the entire chart was stabilised, I fashioned a Melinex folder using an HDS Keeper® ultrasonic welder. The folder gives a primary, unobtrusive layer of protection to the chart, suitable for both storage and transportation.

The chart is now in a stable condition, ready to be gently handled.