Last week the Visual Arts department was pleased to host Ismini Samanidou as Visiting Artist, who gave a presentation about her practice before conducting individual tutorials with full-time students. Trained as a weaver and textile designer, Ismini was born in Greece and is currently based in London. From an initial interest in photography, particularly the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ismini went on study at Central St. Martins, focusing mainly on installation. Her methodical way of working often involved weaving together numerous layers of material on a conventional loom, as well as using various processes and materials-such as cotton or wire filaments-to achieve specific surface effects. The handmade approach demanded a substantial time commitment, often producing one inch of progress per day. After a brief interruption for professional employment-which also involved learning particular skills, such as mastering selvedge-Ismini went to the Royal College of Art to study for a Masters in Constructive Textiles. During this period she extended her concern for surface and texture, often working from photographs to investigate how fabric can be transformed.Introducing different phases in her career, Ismini emphasised the importance of travel and a number of specific locations that had direct and indirect influences on her work. She described breakthrough trips to Antigua and Guatemala, both vividly colourful places, where the patina of the exteriors of buildings or artefacts-corroded pigments, sun-bleached objects, wood and metal-led to a process whereby she would mimic found textures in textile composites and woven pieces. This transfer process formed part of an effort to understand the kinds of compelling surface effects, zeroing in on the affective qualities of contrasting pattern or the aesthetic power of naturally degraded textures or worn materials. By translating photographs of these palimpsests into hand-woven pieces, Ismini employed various strategies, including stitching, embroidery and over-printing. Corrosives were also used, such as devore paste, which is used to restructure or emboss fabric by selectively destroying fibres, distinguishing between cotton and linen, for example, and polyester and silk. Given the prominent role of photography in her practice, it was interesting to note shared terms between corrosive processes and (chemical) photography-burning out or in-leading to questions as to the potential impact of traditional photography, in contrast to digital, being the medium for gathered source material.

Using this type of approach, spending up to ten weeks creating relatively few pieces, Ismini emphasised the importance of making in her practice in general. She underlined that investing hours of labour into the production of complex surfaces and layered structures remained a rewarding and productive way of working. Nonetheless, she soon began to explore the use of digital Jacquard looms, especially once she had taken up a role of Artist-in-Residence at Falmouth University. The residency provided generous access to an on-site digital loom, which immediately impacted on the kind of work Ismini was able to conceive and produce. With the making process made so much faster-a large weaving produced in a few hours-a new approach to thinking about images was introduced, encouraging a more direct and intuitive process, but at the same time adding a demand for quick decision-making and an efficient critical eye. Again using photography as a basis for generating images, Ismini produced numerous pieces involving wall hangings, often installed as site-specific works. Although embracing the creative possibilities of the Jacquard machine was crucially important, it was again stressed that the pieces produced remained unique, one-off artworks; these were not mass-produced items. The digital loom was not used simply as a tool for reproduction but as a means to efficiently progress a complex method of making in order to result in a singular object. Furthermore, this was a conscious decision on the part of the artist, readily acknowledging and celebrating the trace of the hand in even the most mechanised of processes.

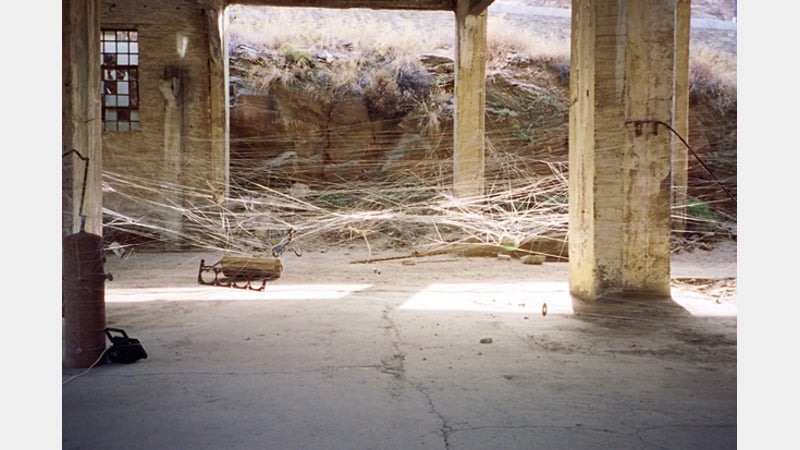

Ismini also spent time describing in more detail a large-scale installation from 2003-The Revenge of Arachne-in which an immense silk web was established in a disused enamel factory on the Greek island of Kea. The work made explicit link to the mythological narrative where the maiden Arachne, a talented weaver, is cursed after challenging the mastery of Athena, goddess of wisdom, weaving and strategy. Having insulted the gods, Arachne is transformed into a spider and condemned, along with her descendents, to weave forever. For Ismini, the installation was intended to "reverse the curse" to present a continuously growing web within the derelict space, yet unexpected twists were to come: local children using it as an eccentric net for improvised football matches, as well as countless resident spiders appropriating the web as a perfect support for their own.

In addition to giving examples of her artistic work, Ismini also discussed issues relating to professional practice and the difficulties in making a living as an artist today. Particularly problematic is the restricted access to looms outside of educational environments. Ismini described the necessity of making contact with various mills, trying to secure working relationships and partnerships. As with many artists, Ismini's practice involves multiple roles and the application of any number of acquired skills and experience. She described how her activities could be divided into several basic categories, including commissions, exhibitions, design development, teaching and research, residencies and travel. These categories would of course interrelate: aspects of the design work-including licencing fabric designs with George Spence Designs or developing commissions for Allen & Overy (Art for Offices) and the Worshipful Company of Weavers-can inform more site-specific public commissions, such as that installed in Godolphin House for Hidden Art Cornwall or developed with the Crafts Council. Ismini's receipt of the 2009 Jerwood Contemporary Makers prize was also discussed, the Timeline project again involving co-operation with Oriole Mill in North Carolina. Working collaboratively was again stressed as a key aspect of Ismini's work, with examples of projects developed with fellow artists, architexts and filmmakers including Sharon Balkey, Gary Allson, and Simon Barker, as well as the sound artist Scanner.www.isminisamanidou.com/