Artist, curator and lecturer Michael Brennand-Wood has a long-standing association with West Dean College, having taught Short Courses and regularly collaborated with the Professional Tapestry Studio, particularly its Creative Director (and Visual Arts Associate Tutor) Philip Sanderson. In the last week of the Spring Term, Michael made a welcome visit to the Visual Arts department to give a talk about his work and to conduct one-to-one tutorials with the full-time students.

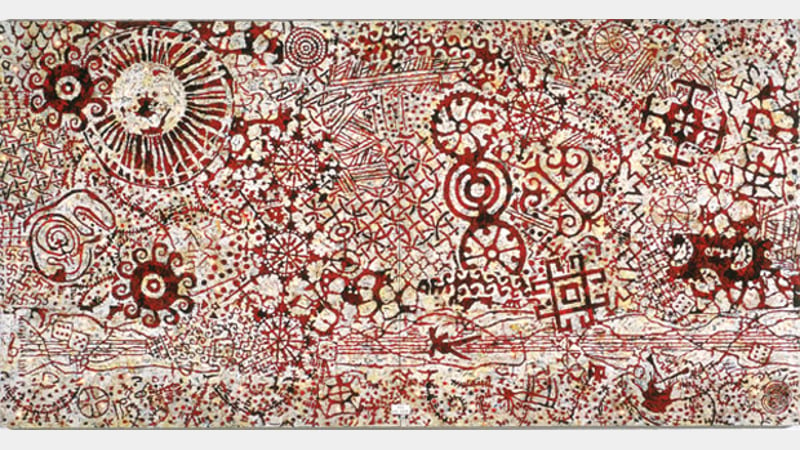

As a broad overview of his career, the presentation covered a lot of ground, fuelled by the enthusiasm, speed and informality of Michael's delivery. Outlining the many influences that have been present his work over the years, Michael picked out a number of consistent themes, including colour and patterning as a specific type of visual language within tapestry work. As he switched between discussions of works made for exhibition, commission and as public art projects, Michael explained that his work often focused around the idea of conceptually synthesising contemporary and historical sources, which he achieves in a number of different ways. From an early interest in collage, bricolage and overlaid textures - particularly in the work of Robert Rauschenberg and Antoni Tàpies, who were both, as Michael put it, "productively disrespectful" in the way they produced their imagery - Michael's work has almost always incorporated the bold use of colour, elements of symmetry and excess, as well as a kind of process that leads to something like an archaeological layering of historically resonant materials and forms - often drawing on textile conventions but not limited to them. Added to these features was Micheal's interest in what he termed "loose geometry", near-grids that approach perfect geometric formality but always fall short. Citing the the influence of major figures from 20th Century modernism and conceptual art including Agnes Martin, Kazimir Malevich and Sol LeWitt, the emphasis behind this concern was for what is handmade, analogue, as well as with the kinds of labour intensive practice that produce richly textured surfaces incorporating combinations of mark-making and forms of patina that start to move into three dimensions.

The variety of influences (or references that are 'quoted') in Michael's work are broad, with the finished pieces becoming indicative of his efforts at locating and acknowledging links between what he is constantly drawn to as an artist. Throughout his practice, copious references to Western popular culture stand out, not only in precedents to be found in the history of visual art but also film and, especially, music. All manner of popular music references abound, whether it be an aesthetic nod to punk or psychedelia, or the type of paraphernalia associated with countless styles of subculture or alternative genre. When talking about his work, Michael would use many descriptors relating to the kinds of sonic qualities to be found in his own musical heritage and upbringing - linking the way his pieces are put together with evocative terms such like 'distortion', 'white noise' or 'fuzz'. At the same time, there were also references to the inspiration of John Cage, both in relation to chance- and process-based work, and the importance influence of repetition and polyrhythmical compositional structures associated with people like Steve Reich, Philip Glass and Terry Riley. Comparison with cinema were also brought up in a number of places, often through the suggestions that the formats of Michael's larger pieces relate to narrative layout, their dimensions presenting screens (or "visual fields") upon which artist's compositions can unfold like storyboards.

Another significant influence came from the Eastern decorative tradition, whether in geometric textile designs or the intricacies of Islamic calligraphy. Michael could be seen appropriating forms like the arabesque or referencing the kinds of symmetrical network seen in exotic carpets. Again this seemed to feed into a wider fascination for superimposed patterns across cultures, even into evidence of fractals, lattices and matrices. Tensions between established visual languages are often set up within Michael's work, seemingly enjoying the aesthetic mash up between areas contested between different cultural contexts, relating to particular industrial traditions, technological innovations or social hierarchies. Michael stressed that, for him, textile is an extremely loaded political medium, inevitably linked with manufacturing technologies, the history of labour relations, and his own family history. Another aspect of these debated areas that Michael was keen to engage in concerned the kinds of gender-specific roles associated with particular materials and methods of making. Citing Rozsika Parker's Subversive Stitch as an important point of reference, Michael related elements of his practice to the connections between embroidery and femininity, crucially via a male perspective. This interest was extended in a series of works exploring lace-making (in one case making a body of original work in response to a collection of 16th Century lace), particularly its historical relation to wealth and status rather than any predetermined gender roles or social expectations.

The introduction of other materials (such as wood, copper and brass - which themselves refer to other kinds of artistic tradition), are part of Michael's extension of the fundamental precepts of weaving. The sculptural meshing of these kinds of 'additional' materials nonetheless constitutes the formation of a ground through warp and weft, but where these basic axes are put into question, as if the artist were trying to establish a bespoke ground that simultaneously gives the object substance whilst laying it open to question. By importing quite unexpected or counter-intuitive materials, Michael can also explore different ways of making his work more threatening. This is a technique that recurred a number of times: effectively seducing the viewer with an ostensibly benign, decorative prettiness (the work exploring floral textiles being a particular case in point) only to conceal a darker content beneath, which is only revealed upon closer inspection. However, such undercurrents of more topical or politically loaded material often bridge the divide between 'surface' and 'depth' - for example, the use of emblematic forms and patterns that are used as graphical shorthand or brand logos essentially shielding an often brutal underlying reality. The use of flags, medals and military iconography is part of this inquiry and constitutes another set of 'icons' that Michael has built up in his work: a collection in which camouflage patterning, the livery of warfare, and the common symbols of commemoration and national mourning occupy the same visual continuum as the accoutrements - badges, buttons and toys - of pop music, video games and cinema.

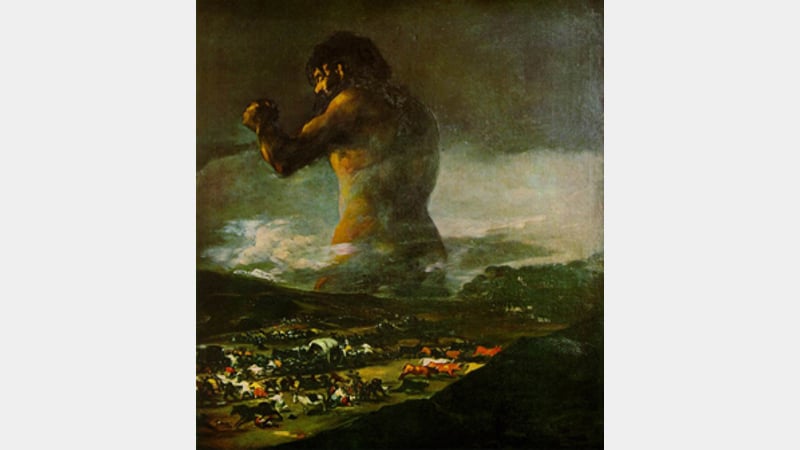

One piece that Michael examined in more detail, Transformer, was a recent collaboration with West Dean Tapestry Studio, made in response to the Bluecoat Display Centre's theme of 'The Heroic' and exhibited at Collect 2012. Michael's original design, which was translated into a woven tapestry by Philip Sanderson, includes a composite figure superimposed with selective splashes of vibrant red and various raised surface textures. In the context of the talk, the figurative element of the piece seemed unusual in relation to much of Michael's other work, yet it was interesting to hear mention of the points of reference that emerged as the piece was developed - including cartoon characters, playing cards and The Colossus, commonly attributed to Francisco de Goya. At the same time, Michael began speculating as to what degree the piece constituted a kind of self-portrait, with the 'space invaders' laughingly interpreted as symbols of conformity. As he explained, Michael is fiercely protective of his independence and seeks to position himself at a relative distance from the commercial art world. As the session drew to a close, with various questions coming from the audience, Michael looked to the future, showing a few developing pieces where painting was much more prominent. Given his present focus, he described his ideal activity in the studio as being "thread in one hand, paint in the other", still reminding us that, as always, he would be urging himself to go somewhere different with each step. The final emphasis of the morning was for art that looked to the past with the same spirit with which it engaged with and reflected its times.