Last week the Visual Arts department was pleased to welcome back artist and educator Peter Webster, until recently based at Falmouth University in Cornwall. Returning to West Dean for the second time, Peter gave a talk focusing on processes of artistic research, using two of his own projects - one recently completed, another still at the proposal stage - to give an indication of how such processes are embedded in his practice. Questions concerning the principles of research underpinning artistic endeavour - for example, the ways in which artists' engage in visual thinking predicated on the formal qualities of their work or the degree to which these processes might be inherent to methods of making - prompted interesting discussions. By taking the audience through the history of particular bodies of work, developed for specific exhibitions, Peter effectively drew out many of the tacit methodologies involved in the development of ideas, practical experiment and critical reflection.

The first project involved an invitation for the Newlyn Society of Artists to work with the archives of Plymouth City Art Gallery, to be exhibited under the title 'New Light on Newlyn'. Peter's first visits to the collection were described as a kind of reconnaissance mission as he sought ways to address the resources available - including work by artists of the historic Newlyn School - deciding how best to make a record of the experience and how he might get a foothold in a body of research. The idea of taking photographic documentation of various paintings proved pivotal, as one canvas in particular began to insist itself. Samuel John Lamorna Birch's Winter in the Roseworthy Valley (1905), a snowbound Cornish landscape striking for its use colour, space and composition, soon lead on to ideas concerning the very nature of images.Birch, apparently led by the demand for fashionable winter scenes, took to recording landscapes of the South West in warmer months before artificially setting them under snows. This false construction (often made with the help of photography) underlined the obvious fact that, however convincingly rendered, representations such as Birch's are simply that - visual constructions of paint on a surface that provide an illusion of depth yet which do not let the viewer beyond its flatness. Birch's visit to the scene was in July, his transformation of it, where he transposed it in time, is a projection. Peter's research process already started to relate Birch's approach to ideas concerning image mediation via dispersal through countless screens, from media devices to the windows of moving vehicles, with an interest in the disruptions of whatever continuum (of convincing 'presentation') such screens claim to give us: glitches, pause-shimmers, flashes of static and noise; losses of fidelity that are now commonplace in a digital world where data is compressed to make its transmission more efficient.RE: WIRV 1, the piece that Peter submitted to the final exhibition (and displayed opposite the Birch), consists of a digitally manipulated CMYK print that re-imagines Winter in the Roseworthy Valley. With a carefully altered version of Birch's original at its centre, the surrounding margins contain glimpses of the room in which the painting was photographed, as well as a colour balance chart used by printers at the top edge. These are not only indicators of production processes but also compositional add-ons, effectively embedding the image into another context with traces of its passage made visible.

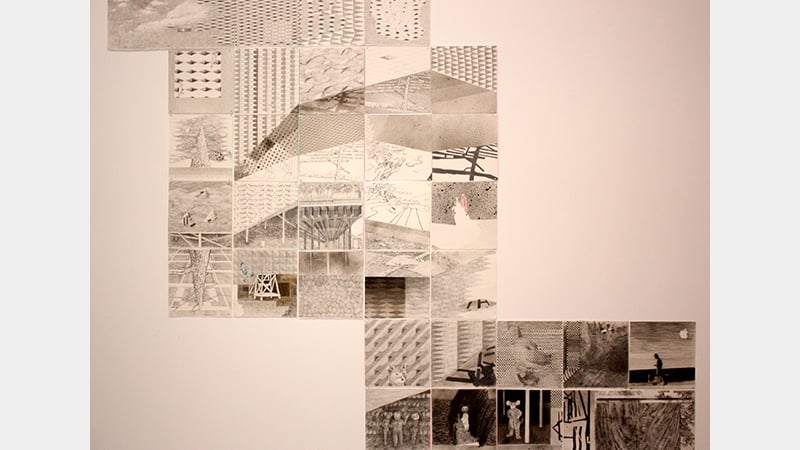

During his discussion of another project proposal, based on an interrogation of his experience as a painter and educator and which prompted a studio visit, Peter then gave a brief survey of his practice. Again the idea was to emphasise the role of research - an array of events that occur when artists seek out things that surprise, revisit sites, images and habits, try to make connections and changes, building up a store of ideas and possibilities. Since the 1970s, Peter's paintings have brought together different visual languages, often mixing high- and low-culture references from the traditions of easel painting to the saturated colours and graphic forms of cartoons. These juxtapositions can be deliberately jarring - one approach moving as an 'ingress' into another - or an extremely subtle part of a layered methodology. With his approach to painting considered a 'modelling' process, Peter would often incorporate three-dimensional forms in his composition planning - making maquettes in low-grade materials such as cardboard, tape, wire and string, etc. which would then be translated into arrangements of paint on a surface, in a sense forcing a transition from one conception of space to another. Central to such techniques was always the tenet of the figure-ground relationship, making planes, surfaces, colours (etc.) recede and approach, at the same time as incorporating references to classical perspective, references from art history (including Giorgione's La Tempesta), as well as the flattening processes and iconography of photography and computers. The insights into Peter's working methods were fascinating and directly beneficial to the students as they continued preparations for their Summer Shows in the Summer.