A few weeks ago, the Visual Arts department at West Dean College was pleased to welcome London-based painter Teresita Dennis as guest speaker. Having trained at the Royal College of Art and Goldsmiths, University of London, Teresita teaches at the City and Guilds of London Art School. During a morning presentation, Teresita gave an overview of her painting practice, marking her concern for connections between the body, the act of painting, and language. Speaking as an artist with a substantial and ongoing interest in the resources to be found in and around theoretical material and philosophy, Teresita's engagement with particular authors and thinkers was a consistent theme throughout the discussion. An account of the development of her work emphasised keys themes, linking the practice of contemporary painting in the context of performance strategies, exploring ways in which material and physical gestures or presences are incorporated into the production of images, with each 'body' of work prefigured by the task of how to embody corporeal affects in visual imagery. Much of the talk focused on concerns as to how painting can constitute or enclose an event, as much as it might 'relate' one through more conventional modes of representation or abstraction. Teresita alluded to the hidden spaces of practice, which for her are closely associated with the role of the body in the act of making, but also the presence of the body as a formative 'sounding board' for all manner of affective sensations that take place through the body (for example, shivering, stuttering, yawning, etc.) and which can inform or provide material for an artistic concern. How might such affective sensations be passed onto the surface of a canvas by means of additive layers of colour and form?

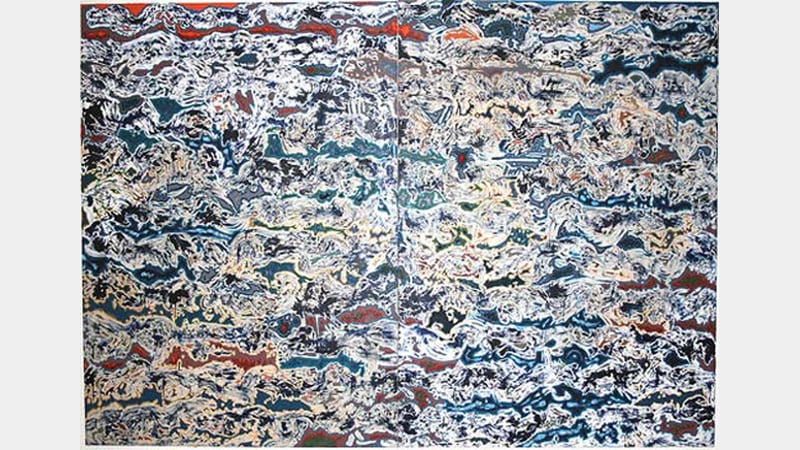

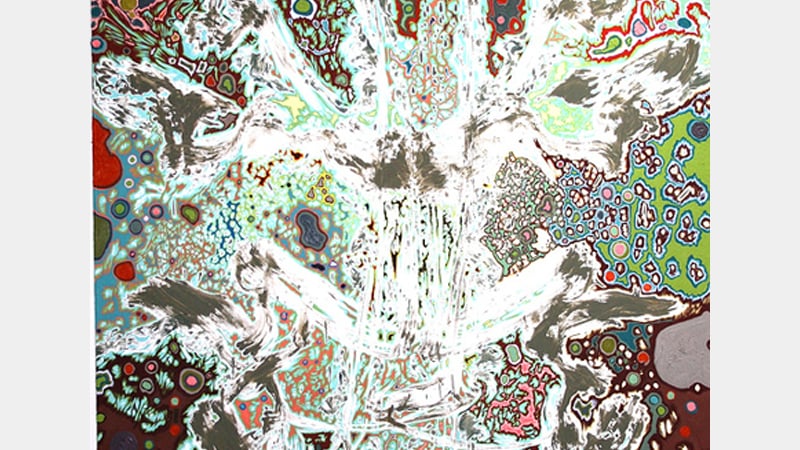

In addition to this type of concern, Teresita also spoke about everyday events―ranging from the traumatic and the exultant in nature―that affect the bodies that live them: influences that might operate on multiple layers, ranging from the psychological, the physical, chemical, and so on. This led into further discussions of method, focusing on the confluence of physical actions in relation to the material qualities and processes inherent in paint, as a conscious extension and questioning of what the language of painting is capable of addressing. Put simply, Teresita's method, in terms of how she harnesses paint, was described in terms of engaging her own body in the mark-making process, whether explicitly using her body to create marks on a canvas, extending the reach of her body with supplementary limbs in order to mediate the distance between body and support (including, of course, the paintbrush), performing simple gestures (repeatedly) to make records of specific movements in the vicinity of the canvas, and so on. For all its connections to performance, however, these acts were not made in public. Instead they were private actions, made alone in the studio. After a trace of the body had been registered in this way, Teresita then worked back into the canvas, confirming forms through the addition of layers of opaque colour, in a way that would, as she put it, "maintain the register" of the original action through a specific palette or paint application. The charge of the colour juxtapositions are a crucial element in the way in which each work occupies space and appeals to the retina. The images are a series of emphatic manifestations that address painting to the realities of experience, including processes of realisation, catharsis and constructive affirmation.

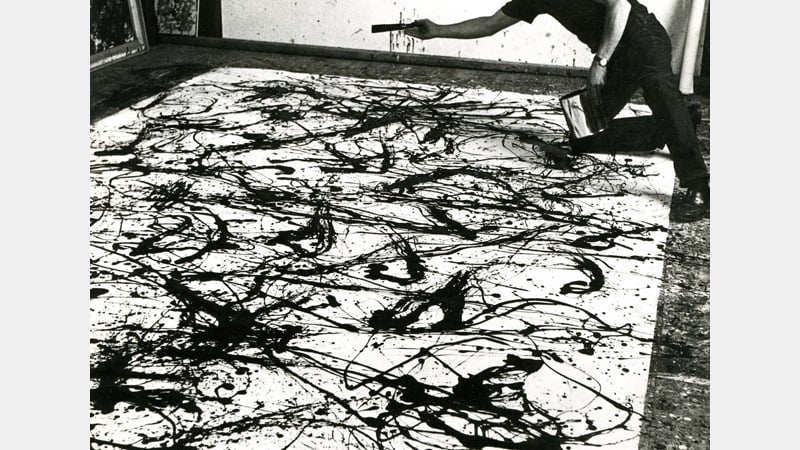

The paintings do convey something directly concerning the anthropometric information imparted onto their surfaces - there is often an image of the dimensions, orientations, scale and reach of a human form (specifically an adult female) - yet part of the territory being examined in Teresita's works would seek to address gaps within those mappings. It was interesting for comparisons to be made to the 'action' painting of Jackson Pollock, not only in terms of the gestural investment and dynamism involved in their production (yet with Pollock, the motions of the artist seem to be 'disembodied' somehow: always being cast outward, away from the torso, etc.), but also in relation to Teresita's particular use of the term "intensity" throughout her talk, which seemed to connect with her interest in the 'all-over' aesthetic described by Clement Greenberg in relation to the work of Pollock and others.

Although the corporeal was inscribed in the images to a greater or lesser extent, the subsequent processing of those initial marks often involved covering the whole canvas from edge to edge, such that a combination of the intensive and the expansive are at work in the different stages of each painting. As well as Pollock or Tobey's 'all-over' canvases, another useful reference might be Yves Klein's Anthropometries (c.1960) a series of performance-based paintings produced using women as 'human paintbrushes'. These works were both gestural and theatrical events staged in front of an audience, surrounded by signatures associated with the presence of Klein as the artist-conductor: the use of an original, artist-patented colour blue; the performance being accompanied by music Klein had composed ['Monotone Symphony' - a single note played for twenty minutes, followed by twenty minutes of silence], adding to the radical-formality of the performance.

The 2012 Tate exhibition, 'Painting After Performance', explored how different strands of performance had informed painting practice, exploring major categories of the 'gestural' and the 'theatrical'. It's interesting to consider where Teresita's practice might fit in with such distinction, especially since, there is still in Teresita's work a firm commitment to established practices and conventions of painting: primed canvases, coloured grounds, vertically and horizontally oriented supports, and so on. Yet in relation to the concerted thinking about the constitution of an event in painting, especially in relation to theoretical and philosophical reflection, it might be interesting to also consider the work of British artist John Latham, particularly in his use of a spray gun in making 'process sculpture'. Exemplified by Full-Stop (1961), these works were, for Latham, a way of trying to understand time and matter through what he called a "unifying atemporality", taking the accretion of multitudinous points (released by the spray gun action) as an atemporal action, thereby marking a conscious distance from the gestural action painting of that time (including Pollock, for example). As a work concerned with the emergence of matter in empty space - an interplay of figure/ground (dot/field), where atomised fragments explicitly relate to a cumulative whole; where fixed and blurred edges coalesce; where the differences between dots and points emerge from a semi-mechanical process that relates more to printmaking than to painting; a concern for language, grammar and the written word underlined by the title - Latham's work adds multiple dimensions to the ideas concerning the painting-event but perhaps crucially, at least in relation to Teresita's work, disconnected from the body.

As already made clear, the body has been central to much of Teresita's work. Whether it be in the simple, repeated gesture of pigment being cupped in the palm and then systematically released across a receptive surface, it is often in a combination of controlled actions connected to semi-abstracted and aleatory results. As her practice developed, Teresita suggested that the central spurs for the paintings were no longer traumatic, but were tuned in to more ordinary experiences, especially those of reading and writing. Of course these are events too, as well as being made up of countless sub-events, and the interest is in just how thinking that passes through material parts of the body and how the constructed image can appeal to boundaries between marking and saying. A series of paintings with a cleaner, crisper approach (precise overpainting) soon emerged, still with an emphatic choice of palette with vibrant combinations of tone, again with subtle insertions of anomalous points of colour - their edges exciting one another, playing off the ground.