By Peter Pearce, Chief Executive of the Edward James Foundation (2012-2015).

In 1989 Uppark burned down. At the time, I was the National Trust's Managing Land Agent for its West Sussex properties, and Uppark was my responsibility. I had drawn up and signed the contract with the builders who caused the fire (which started from lead workers ignoring carefully drafted "hot work" rules against precisely this risk). Consequently, this disaster did not feel like a good career development. At 6 AM on the morning after the fire started-while the house was still burning-I was appointed to direct the project to restore it, which ultimately took six years.

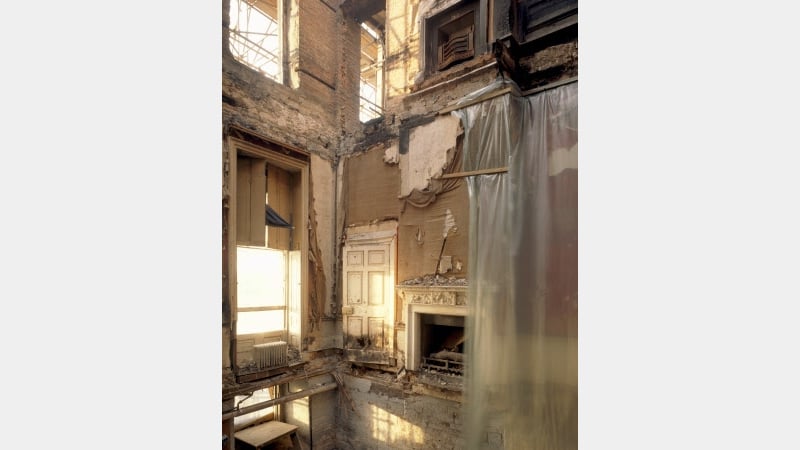

For those who don't know it, Uppark is a magical late 17th-century mansion building poised on a shelf of the South Downs looking far out over the Solent. It is well worth a visit for anyone interested in conservation. It is one of the Trust's most important and loved houses, particularly prized for its fragile and delicate unchanged interiors through which this devastating fire ripped.

The fire galvanised the largest conservation exercise ever undertaken by the National Trust, calling in all its expertise and resources. The result was a truly inspiring exhibition of 20th-century conservation which gave back to the house its atmosphere. All the more remarkable, this had to be achieved in the pressured timescale of an insurance-funded contract, not conducive to patient and painstaking conservation. Everything possible was competitively tendered for this reason. We knew that every decision taken on the ground would eventually be fought over in court with the barristers for the builders' insurers, something which concentrated the mind. (The case, which hinged on insurance law, was fought right up to the House of Lords, where the Trust and its insurers eventually succeeded handsomely. It generated over four tons of paper.)

There were many remarkable stories of conservation victories and achievements, many lessons learned and areas of conservation where new ground was broken which has benefited later victims of fire (as indeed did Uppark, from the lessons learned from the fire at Hampton Court some years earlier; our lessons were in turn put into practice at Windsor Castle's fire). In this short piece it is impossible to do justice to these achievements; but here are a few examples.

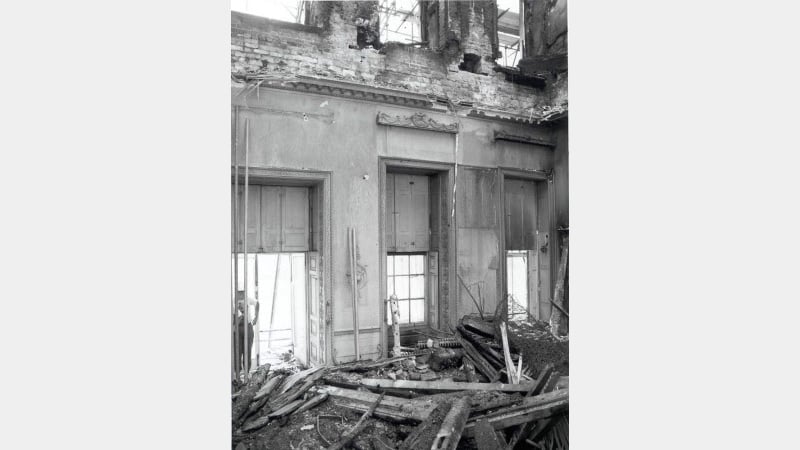

After the fire, the house was four feet deep in wet ash and rubble. (It was open to the sky from every ground floor room.) It was gridded in the manner of an archaeological site to record where each cubic metre of ash came from which was then stored in 4000 plastic dustbins, later reused at Windsor Castle, to be put through a giant riddling machine developed by the Ministry of Defence to sift out bomb fragments. This extracted an extraordinary amount of mainly architectural detail; window and door brassmongery, precious fragments of gilded and gessoed architectural woodwork, even fragments of damask wallpapers. The lesson; never throw anything away. Most of this material eventually went back into the house, far more precious than a replacement. Furthermore, the high cost of making copies meant that conservation was often cheaper than replacement, which meant there was no argument with the insurers; philosophical and financial considerations aligned.

There were five wonderful late 17th-century and 18th-century stucco ceilings to the groundfloor rooms reduced to several thousand fragments, most extracted from the ash. To recreate these against an insurance-driven timetable which allowed less than a year from a standing start, with not enough skilled conservators and stuccoists for the timescale and a desire to keep and refit decorative (often gilded) fragments into the new ceilings like plums in the pudding, was hard enough; but then the main contractor went bust at the critical point. Somehow we kept going, kept the stucco team together and ceramic artists were recruited from advertisements in art magazines to apply their skills in this new way. Paterae, dentil cornice blocks and run plaster mouldings were copied from surviving material; and the skills of applying stucco and running lime plaster cornices learned working upside down, like Michelangelo, in a large tin shed on-site with many mishaps along the way. The end result was astonishing, proving beyond doubt that the apogee of these skills in the 18th century could be matched in the 20th.

West Dean played its part in this story providing craftsmen and women, expertise, facilities and support. Many of the conservators who worked on Uppark were trained at West Dean and developed their skills there, going on to greater things. In some cases, new companies were formed arising from working at Uppark. All this goes to show not only that even the most desperate cases of damage can be brought back to life for future generations, but how precious are the skills to achieve that-and how essential it is to train the next generation of craftsmen and women.