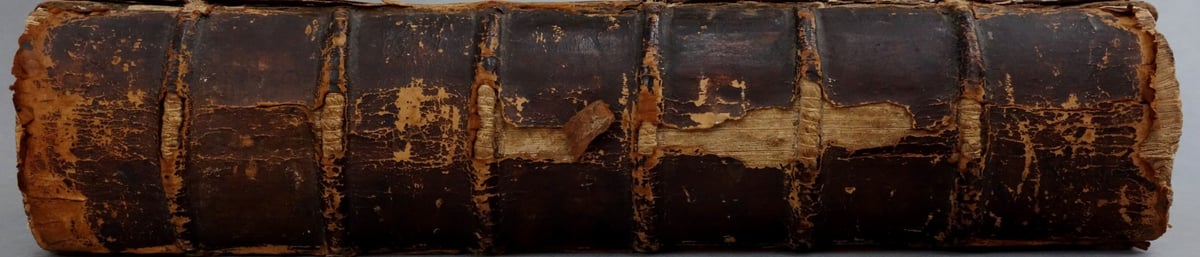

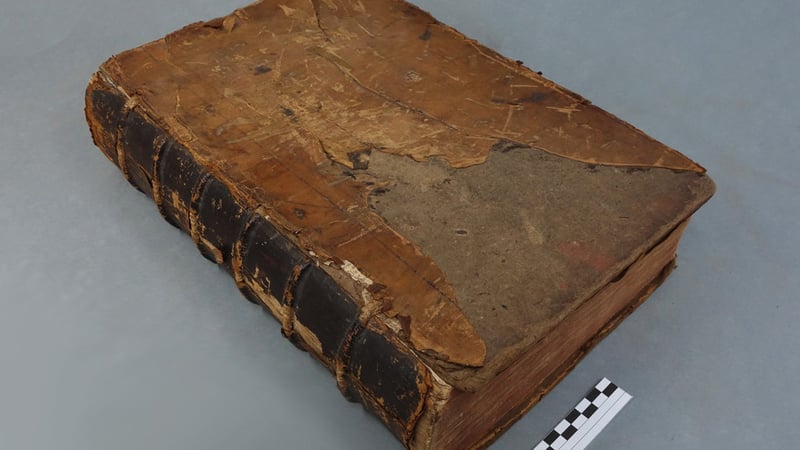

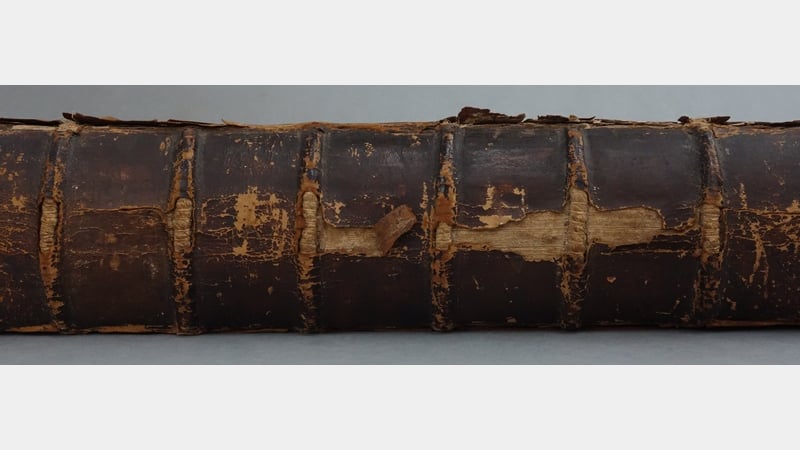

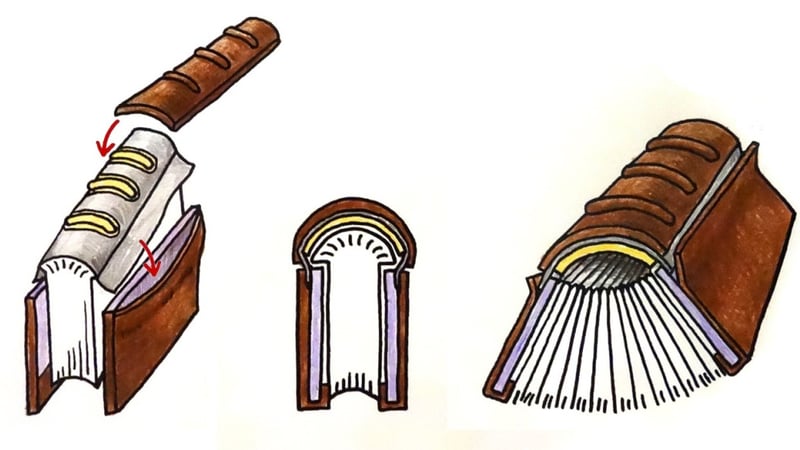

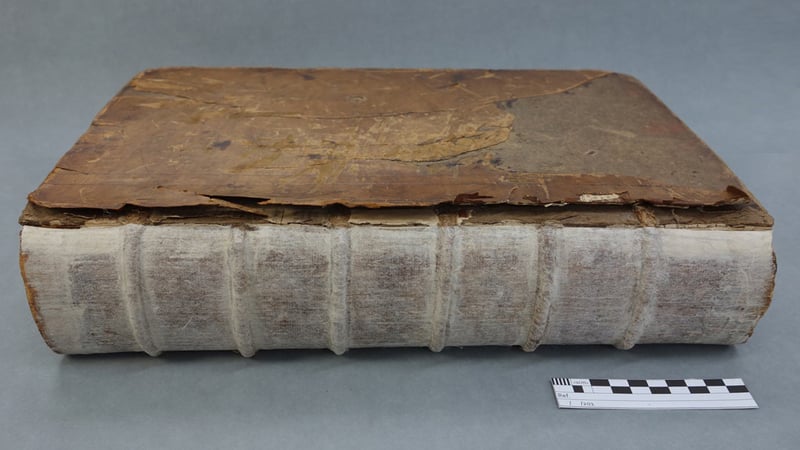

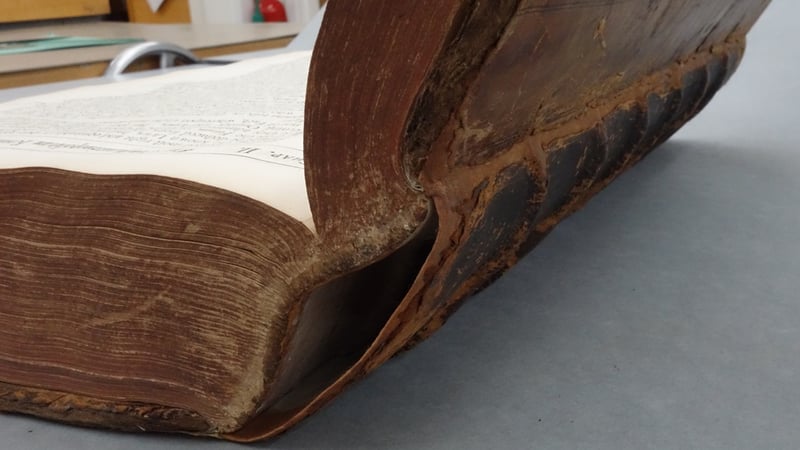

A typical issue of tight back bindings is that they expose the book spine to increased mechanical stress and limit the ability for the book to open flat. These issues are amplified by the size and weight of the volume and by the grammage of the textblock paper.

This was exactly the case of the History of the World. The structure made the book difficult to open, and over many years of usage, the huge tension it had been exposed to had damaged the spine leather. Moreover, continued usage was very likely to create further structural damage, not only to the spine leather but also to the textblock itself.

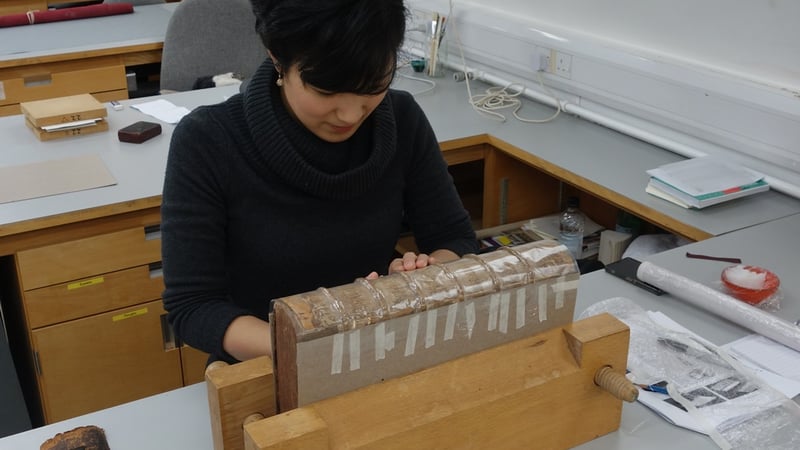

How do I tackle this problem? This was not a straightforward decision, and I had to find an acceptable balance between the ethical tenets of "minimal intervention" and the practical requirements of "functional recovery."

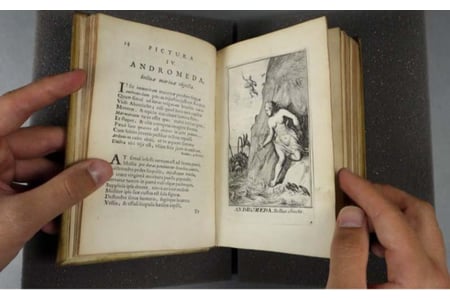

Let me explain. Conservation theory and most professional guidelines tell us that treatment decisions should be guided by the concept of "minimal intervention". This concept is inherited from the world of "fine art" conservation and tells us to put the integrity of the original object first and to restrict treatments to the strict minimum necessary to protect it against damage. According to this guidance, a conservator should not attempt interventive "restoration" of an object by reconstructing missing areas or recovering damaged areas, but only to stabilise the material and limit further damage.

But books present a major challenge; they are very rarely art pieces solely for display, but functional objects that will need to be manipulated and read after treatment. This means that in many cases, limiting a book treatment to "minimal intervention" leads to a major loss of function: the book cannot be practically used and read, OR is exposed to high risks of damage if used. Because of this, book conservators often have to consider far more interventive "functional recovery" techniques, not only to repair existing damage but to protect the book for a future "active life".

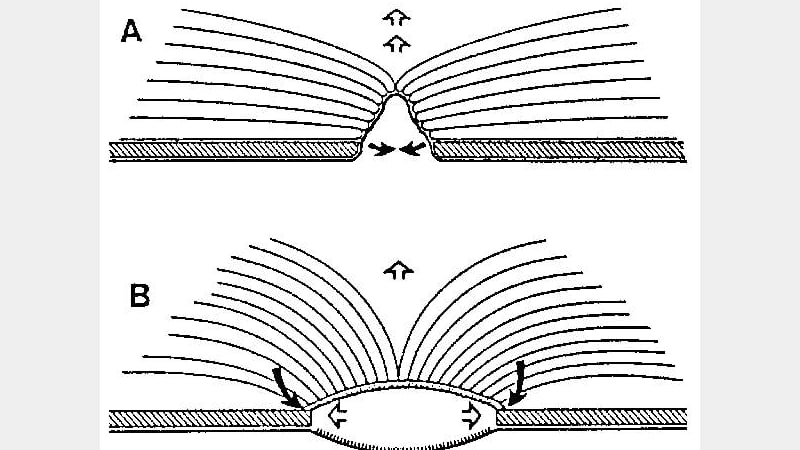

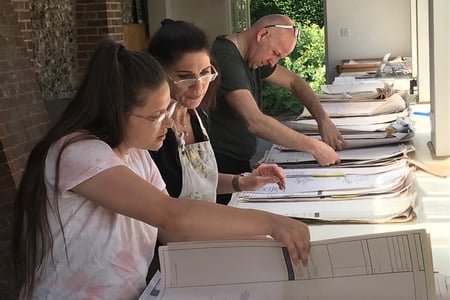

The challenge, on a case by case basis, is to find the right balance of techniques to both protect the object as a historical artefact and as a functional object. The condition of the book, the priorities of the client, the relevant techniques and the budget available all participate in this complex decision process. In this case, as illustrated below (Fig.5), I had a wide range of options to choose from, ranging from a "do nothing" cop-out to a very aggressive and interventive complete rebinding of the book with new material.