Stop and smell the roses: cleaning a 16th century German herbal

- By Megan an MA Book Conservation Student

There is a box on my workbench that, when opened, displays four smaller boxes. If you open any of these smaller boxes, the contents look astonishingly like the inside of a box of After Eights, with all the chocolates lined up in their little packets. Rather than minty treats, these boxes contain what my colleagues jokingly refer to as my collection of dirt, the many and various inclusions found in the Kreuterbuch, a 16th-century German herbal.

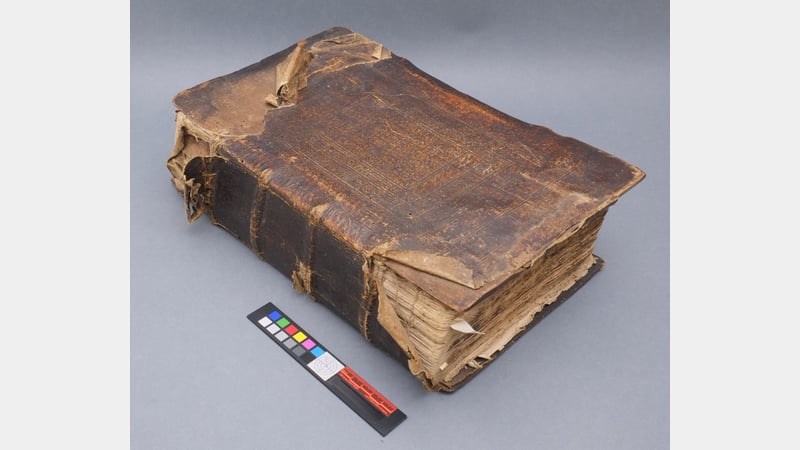

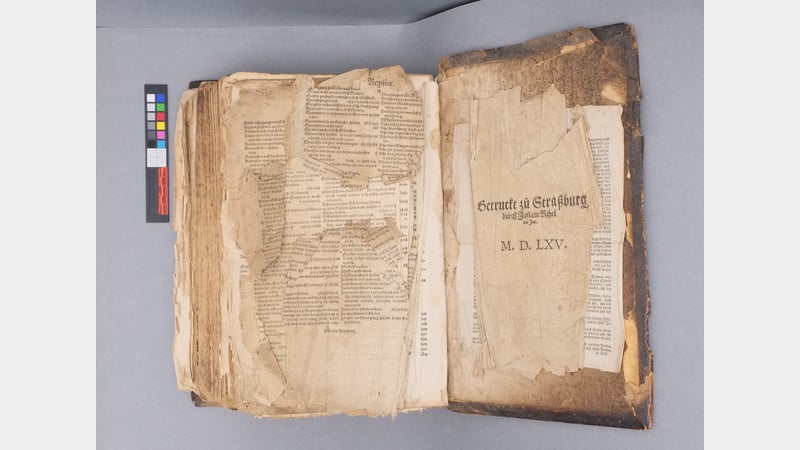

As a master’s student in book conservation at West Dean College, you are expected to choose several projects to conserve throughout the year. Instead, fellow student Amy Randall and I found ourselves admiring a 1565 German Kreuterbuch, or herbal, the treatment of which would prove to be such a complex project that we decided to take it on together over the course of the entire year. Let no one say that either of us backs down from a challenge!

The history behind the Kreutterbuch

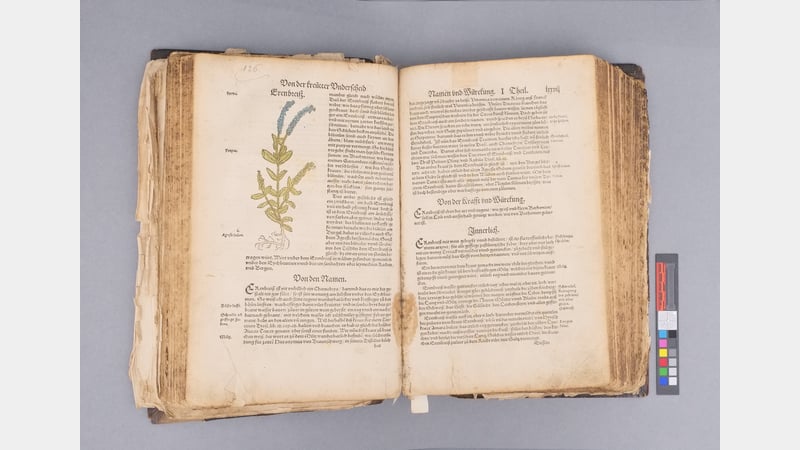

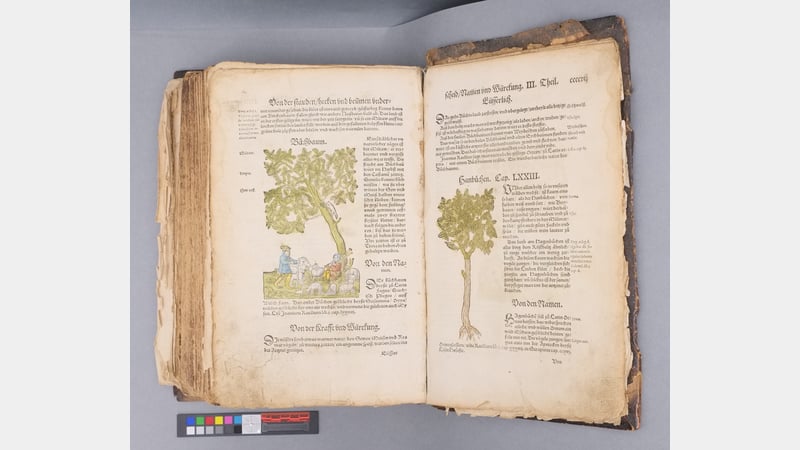

We began by exploring the book’s history and binding. The author, Hieronymous Bock (not Bosch, so no depictions of Hell!), is considered to be one of the German Väter der Botanik (fathers of botany). The artist of the beautiful woodcuts that occur on almost every page, David Kandel, was one of the first botanical illustrators. He was also probably the printer, and the woodcuts are much finer than would be expected for this time. Amy, armed with J. A. Szirmai’s The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding and Julia Miller’s Books Will Speak Plain, diligently went through the binding, finding that each detail matched with what would be expected of a 16th-century German binding. We were absolutely thrilled when a furniture conservation student took one look at the exposed left board and announced that it was beech, which, according to Szirmai, is the most common wood for German Gothic bindings.

As exciting as it is to have an early (possibly original, though it’s very hard to say for certain) 16th-century book binding, it comes with difficulties. There were tears throughout the book, and the pages were thin and fragile in the lower corner from centuries of being turned, even having worn through in places. More alarmingly, the first and last few signatures (groupings of folded paper that can be sewn through to connect them together) had torn away from the sewing, leaving the pages loose, badly creased and torn. Before we could tackle any of this, though, we had to decide what to do about the dirt.

Books are meant to be used. This means they get dirty: who hasn’t dropped crumbs on a book at some point? Nearly-500-year-old books are dirtier than most. Nearly-500-year-old herbals, which were used to identify plants, are dirtier still! Various things had ended up giving the Kreuterbuch its rather grubby appearance. Several gutters contained a black, sooty material. Insects had been squashed between some of the pages. Slips of paper, parchment and textile fragments had presumably been used as place markers. There were a few larger paper inclusions too, including a 20th-century Swiss fitness advert and a 16th- or 17th-century advert for a doctor, also apparently from Switzerland. At some point in its history, numerous plants had been pressed into the book. Many of these have since decayed almost entirely, with only seeds or straw-like stems surviving. Some were still identifiable as plants, and one or two surviving flowerheads even appeared to correspond to the woodcut images on the pages they were pressed between, however, they were extremely fragile and vulnerable.

Inclusions such as these tell a story, showing how the Kreuterbuch was used and even which parts of it were more heavily accessed. Some pages had noticeably less dirt accumulation than others. Removing the inclusions—even the material which had decayed to dust—meant removing information about the book’s history, but at the same time, they were causing a problem. We needed to carry out paper repairs to stabilise the torn pages, but doing so without cleaning them first risked trapping the dirt and preventing the repairs from sticking properly. There was also the fact that the book didn’t look well cared for, which could lead to the object not being handled carefully in the future. Combined with the fact that the plant material and place markers were vulnerable to being lost, it was clear that we needed to do something.

The restoration process

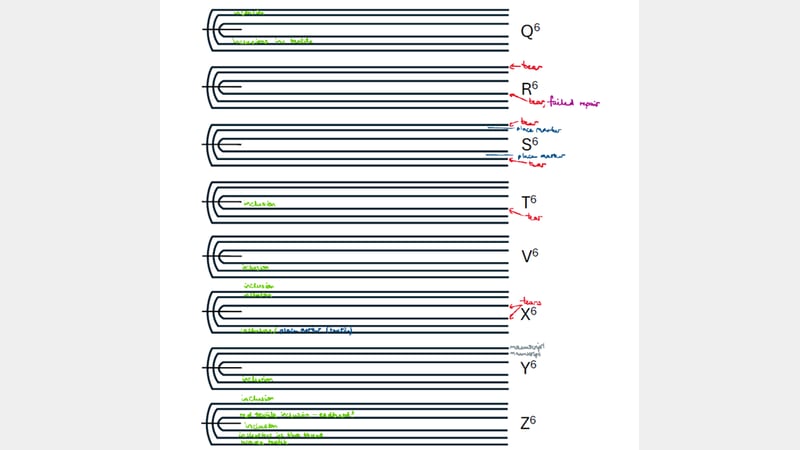

The first thing to do was to record the key inclusions in the book. In fact, we went a step further than this and created a signature map, recording the location of loose pages, tears, historic repairs and stains as well as inclusions. We didn’t record loose dust/dirt since it was found throughout the book, and we knew every page would need cleaning to remove it. From our signature map, we were able to identify the different materials we were dealing with and could consider the best way to house them.

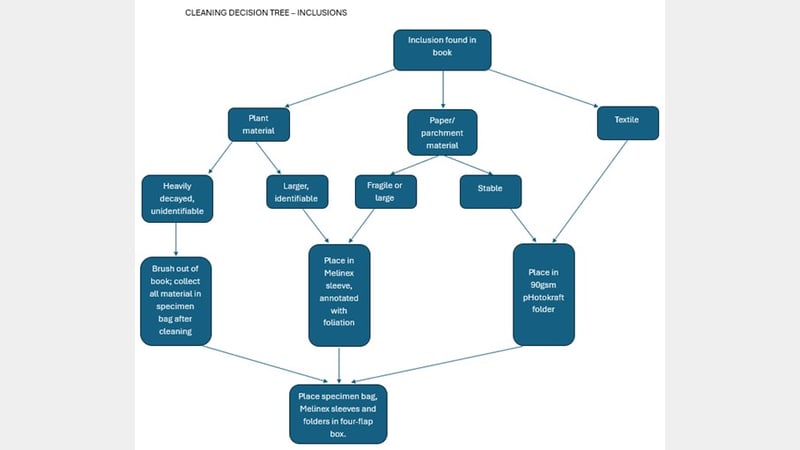

Referencing our map, we organised materials into three categories: plant, paper/parchment and textile. The plant category was broken down further into ‘heavily decayed’ or ‘larger, identifiable plant material’ and the paper/parchment category into either ‘fragile’ or ‘stable’. Larger, identifiable plant material and fragile paper would be housed in Melinex sleeves, and more stable paper and textiles would be housed in acid-free paper (Heritage Archival pHotokraft) folders. The unidentifiable, heavily decayed material was brushed out of the book and collected into a specimen bag (yes, this means I have a bag of dirt). To record and display this process clearly, we created a decision tree with a flow chart showing how any given inclusion would be treated. This also proved to be very useful for the two of us, to ensure we treated inclusions consistently throughout the cleaning process.

Having decided a) that we did need to clean the Kreuterbuch and b) how to do so, the work began! First, we made a stash of both paper and Melinex folders, all cut to the same size, to help make re-housing inclusions go smoothly. For larger paper inclusions, we created a set of bigger Melinex folders, and when a couple of the place markers proved to be even larger than our prepared folders, we custom-made them as needed. Whenever an inclusion was placed in a folder, we recorded the two page numbers it was found between on the front of the folder in permanent pen. The book was cleaned in a large tray made of Heritage Archival pHotokraft paper which collected the brushed-off dirt, and, at the end of each day’s work, the dirt was swept into the plastic bag.

By the time we’d worked our way through the whole textblock, it was clear that we needed to come up with a clever way to store all these little folders, which were in a heap between our two workbenches. Because of the way we had created the paper folders, it was difficult to stack them together without the pile toppling over which would risk the folders getting out of order or even being lost. Clearly, one stack wasn’t going to work. We noticed, while playing with the arrangement of smaller stacks, that the book’s width was about equal to the width of three folders side-by-side. Storing the folders in three stacks would make it easier to house them with the book once we finished the conservation treatment.

The housing process

The paper folders and the Melinex folders didn’t stack together easily, so we separated them out. Those made of paper were about twice as bulky as those made of Melinex, simplifying our decision for how to divide up the stacks. Both piles of folders were put in order, according to the page numbers they were found between, and then divided in half. We then put each of the four resulting stacks in its own box made from acid-free folding boxboard. The boxes for the Melinex folders were half the depth of those made for the paper folders, so when they were stacked together, they took up a third of the space. We divided up the Melinex folders as well to make it easier to locate any given inclusion; each box has the range of page numbers written on the front.

The folders for the larger paper markers didn’t fit in the small boxes. To accommodate these components of the inclusion collection, we made a large housing box from acid-free folding boxboard, which could accommodate the small boxes, and inserted a piece of Plastazote cut to fit in the base of the large box. We then hollowed out the Plastazote base allowing the larger paper marker folders to lie inside with the small boxes resting above on the Plastazote lip. Now, when you open the housing box, you find the four small boxes of folders sitting neatly on the Plastazote base with the larger folders nestled below. The big Melinex folders with the largest paper inclusions and the plastic bag of dirt don’t have their own housing yet; that will come when we have finished conserving the book and can make a drop-spine (clamshell) box to house everything. For now, the inclusions are all safe, protected and organised—a tidy solution for a collection of dirt!

Originally published in News in Conservation, Issue 108, June-July 2025, pp. 36 - 41